INTRODUCTION

Over the years, the conventional process of making staffing changes on the heels of an acquisition has taken one of two forms. Sometimes the acquired firm steps in early to make people changes, whether in just a handful of positions or with wholesale reorganization. In the other approach, the parent company attempts to maintain a hands-off stance again, except for perhaps one or two initial changes until several months have elapsed that hopefully allow enough time for everyone to calm down and become adjusted to the situation. One of the familiar steps in this second tactic involves assurances from executives in the parent company to the effect that, “We don’t plan any personnel changes.”

In both of these approaches, however, the critical element that’s missing is a systematic, incisive assessment of what the acquisition brings vis-à-vis management and technical talent. Typically, the acquiring firm will take a piecemeal approach, wherein a few people here and there are evaluated in a professional fashion. Or a number of people may be appraised in a sketchy manner but so superficially that much room remains for potential problems to develop.

Top management in the acquiring firm might argue that it is best to allow some time for them to get to know the abilities and potentials of the management team in the target organization. But that assumes that those people will hang around long enough for such a familiarization process to occur. Often they do not. Furthermore, while taking the slow route, a part of this getting-acquainted exercise may consist of seeing bad management decisions being made, mistakes that could have been prevented. Likewise, key opportunities may be lost. All in all, this can prove to be an expensive and time-consuming education process. This approach also drags out the integration of the two firms. It forestalls needed resolution and leaves questions unanswered, prolonging the anxiety and ambiguity, thus contributing to the chronic problem of post-merger drift.

This approach is not necessarily a kind and thoughtful way of dealing with staffing matters. Nor is it likely to be viewed favorably by people in the acquired organization. Rather than looking on this as a fair and equitable opportunity to prove themselves, they will more likely be anxiously waiting to see when and where the axe will fall.

The situation feels like benign neglect to people in the acquisition, as if they are being left to dangle helplessly in the wind. In their opinion, it would be better to get closure, to be appraised promptly and fairly, so that they can get on with their careers either secure in the merged firm or somewhere else.

Why Should Incumbents Be Evaluated?

It might be argued that in several merger scenarios it is best to go with the status quo—that is, move on the premise that the incumbent management team is sound and that the acquiring company should not fool around with something that’s working. This line of reasoning sounds good on the surface, especially if the acquired firm is financially healthy and has a pretty good track record. Upon careful scrutiny, however, it proves to be flawed in a number of respects.

Some Incumbents May Not Play to Stay

To begin with, the acquirer needs to ascertain who plans to remain on board. The new owner may be extremely fond of the new charges and fully confident that they can continue to operate the company in a successful fashion. But that’s no guarantee whatsoever that the feelings are reciprocal. Even if these incumbents are not grumbling, even if they appear to be reconciled to the situation, in-depth data gathering often proves otherwise. The acquirer should rapidly identify fast-track, high-talent employees so that the parent company can put forth special efforts to retain them. Often these people can be “hooked” with heavy-duty assignments and special developmental opportunities that clearly communicate the key role they can play in the organization’s future.

It is particularly important for the new owner to take pains to identify these people and tie them to the organization if the acquisition represents a move by the parent company into new terrain, for example, unfamiliar products/services and different markets. The less one understands the business that has been bought, the more crucial it is to keep those people on board who do have a firm grasp of what it takes to make the business a success. The same general idea holds true, of course, if the acquirer does not have any surplus management talent to speak of that could be sent across to manage things in the event key vacancies develop in the acquisition. And after an adversative merger battle has been fought, as in a raid or contested situation, the question of who is willing to stay is a particularly sensitive issue.

Some People Should Be Repositioned or Terminated ...

Related Articles

Job status notification is a difficult challenge that warrants careful planning and handling. Avoid the following typical mistakes when communicating job status information following the close of the deal:

Mistake # 1: Not being prepared.

Antidote: Get ready.

- Know specifically what your role and responsibilities are regarding this process.

- Thoroughly understand the three different categories of employees (continuing, transitional, and separated) and review the process for dealing with each scenario.

Mistake # 2: Not acting calm and relaxed.

Antidote: Be confident.

- As a leader, it is your job to make people as comfortable as possible throughout the job notification process. If you act calm and confident, they will be more likely to mirror your demeanor.

- Make eye contact when communicating the employee’s job status.

- Make sure your body language is relaxed and calm, yet confident.

Mistake # 3: Talking too much.

Antidote: Stick to the script.

- Be sure not to ask unnecessary questions that complicate the dialogue or lengthen the process. While questions are normally a good way to build rapport, this conversation is not the time to explore how the person is feeling or what they are thinking.

- Emotion may prevent people from listening as well as normal, so be clear and concise. Speak a little more slowly than you normally might.

- Remember that this conversation is not a debate. The decision has been made and you are simply responsible for communicating that decision effectively.

Mistake # 4: Spending too much time.

Antidote: Be brief.

- Job status notification conversations should be brief; no longer than five to ten minutes at most.

- You are only responsible for communicating the job status decision, not all the details of separation, outplacement, transition agreements, or job offers, so just make sure you handle the actual decision communication well.

- If the employee refuses to leave or continues to ask questions beyond what is productive, simply say, “I’d like to end this meeting now. We have other resources that will answer your questions and help you with your concerns.”

Mistake # 5: Trying to be a specialist.

Antidote: Be an authentic leader.

- Don’t try to explain details you don’t fully understand. HR specialists will be present to cover the more complex questions related to benefits and compensation. They will also support you with responses to questions about transition agreements and job offers.

- Focus your time and attention on being an expert on the notification process, the quality of communication, and the interpersonal skill required to conduct these conversations with dignity, respect, and professionalism.

- By honest and authentic. If the employee asks questions you can’t answer, make a note and commit that someone will follow up with a response as soon as possible.

Mistake # 6: Responding to emotion with emotion.

Antidote: Be calm and compassionate.

- Be prepared for emotional reactions. You can expect a full range of responses, including denial, anger, fear, sadness, curiosity, frustration, confusion, and/or relief.

- Don’t try to prevent people from feeling these emotions. Emotions are there to help people work through the transition they are experiencing, so you should allow these emotions to do their work.

- Just make sure that you don’t allow their emotions to escalate your response. You may become the target of their emotion temporarily, but don’t take it personally. Just take a deep breath, compose yourself, and demonstrate respect and compassion for the pain they are feeling.

Mistake # 7: Feeling guilty...

Related Articles

Introduction: Job Hunting

Frankly, almost all of us are amateurs at it.

If we find ourselves needing to make a career move, we may pick up a book about job search and start cramming. We might check out a couple of websites for advice on resumes or how to interview. Maybe we attend a workshop to learn techniques for finding employment.

Of course, most people just feel their way along until they land a job offer. And they make a lot of rookie mistakes.

It’s not that job hunting is so complex. It’s just that we don’t do it on a regular basis.

Actually, searching for a new job is a game of fundamentals. We’re not likely to score with some trick play, but rather by mastering the basic “blocking and tackling.”

This handbook boils down the latest job-related research and gives you the know-how you need. No more “winging it.” No more wasted effort on a time-consuming, trial-and-error approach. Here’s the hard-core truth about job-hunting practices that ...

Related Articles

Stay Bonuses Only Motivate People to Stay.

Here’s how the familiar story unfolds…

Company A acquires/merges with Company B. Part of the logic driving the deal is that, in combining the two firms, headcount can be reduced. Accounting runs the numbers and promises annual payroll savings of, let’s say, $20 million.

But, of course, you can’t afford to let all those people go immediately. Some of them will be needed to help do the heavy lifting during the integration process. A few of the folks have critical skills…or they possess key information that has to be transferred to other employees who’ll remain. So, in order to keep the integration from going off the rails, you offer a big chunk of money to select people, the bonus to be paid only if they help out for a specified period of time.

Sounds practical. But research shows that stay bonuses can produce unintended consequences. You could be buying behavior you don’t want. In Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel Pink offers this conclusion: “Do rewards motivate people? Absolutely. They motivate people to get rewards.”

So-called “if-then” motivators (e.g., “If you stay and help with the integration for five months, then the company will give you a $20 thousand bonus.”) often reduce the depth of people’s thinking. These techniques tend to focus people only on what’s immediately before them rather that what’s off in the distance. This myopic attention to short-term gains—the bonus—doesn’t guarantee good decision making. Will your bonus recipients lose sight of the potential devastating long-term effects of their actions?

Pink goes on to list The Seven Deadly Flaws of using extrinsic motivators, the traditional “carrots and sticks”:

1. They can extinguish intrinsic motivation.

2. They can diminish performance.

3. They can crush creativity.

4. They can crowd out good behavior.

5. They can encourage cheating, shortcuts, and unethical behavior.

6. They can become addictive.

7. They can foster short-term thinking.

Stay bonuses don't motivate people to excel.

Related Articles

Traditionally the merger due diligence process has focused on legal and financial issues—e.g., contractual matters, litigation points, economic and fiscal considerations, etc. Obviously that’s an important exercise.

But when mergers fail, as they too frequently do, the odds are it reflects a sloppy job of leadership due diligence.

There is powerful logic in favor of systematically assessing the competencies of key players in the new organization. You should not automatically assume that people who have been successful in a pre-merger environment will perform with the same effectiveness under a new regime and in a different corporate setup. People’s strengths often become weaknesses during a merger transition period.

|

IT IS NOT UNUSUAL FOR AN INDIVIDUAL TO BE AN ALL-STAR IN A SLOW, DELIBERATE SETUP STYLE OFFENSE, YET BE A LOSER IN A FAST-BREAK GAME |

Ordinarily, the most staunch defenders of the old culture—i.e., the loyalists—have the most difficult struggle adjusting to the inevitable changes brought on by a merger/acquisition...

Related Articles

This is the most traditional approach, and it is good so far as it goes. Certainly, it does pay respect to salient—even critical—data. But good numbers can mask weak talent. The acquired company may for all practical purposes have been a one-man show. There may be no backup. That in itself is bad enough, but it becomes even more critical if the front man happens to depart in the aftermath of the acquisition.

There are too many external biasing factors that deserve consideration for the acquirer to simply assume that incumbents truly do deserve full credit for the current set of numbers. A quantitative analysis can be misleading in a variety of ways.

A Product of Good Times

A benevolent economy may deserve most of the credit for the acquired firm’s good financial performance. So the question that deserves thought is whether there is much proof that incumbents can manage a down economy or a post-merger situation successfully.

Short-Term Perspective

Management may be guilty of mortgaging the future to achieve short-term results. Statistics that look good today may have been achieved at tomorrow’s expense.

For example, the financial ledger may look good because there has been no money spent on R&D, capital improvements, and so on. The workforce may have been slashed to cut overhead, but this may have been done at the expense of adequate servicing of the company’s products. And, given time, these sorts of executive decisions could conceivably prove devastating to the firm. Numbers that look good on the surface may actually be fragile evidence of executive talent. Management may have built a house of cards that faces a shaky, uncertain future.

The Hand of Fate

Pure luck may have been on the company’s side. Chance timing may deserve most of the credit, as management simply may have stumbled into good fortune. Or a foolish gamble may have worked, although it never should have been taken.

The trend that has buoyed the financial picture may be about to reverse–for example a fast-growth strategy may be on the brink of corporate wreckage, with financial resources overextended and management capacities strained beyond reason.

Undeserved Credit?

It is possible that good numbers result primarily from the backup strength given by managers or technically skilled individuals who have already left the firm or who probably will leave. Likewise, managers or technical people may have been in slots where their own effectiveness has been masked by the strong or weak performance of another person.

In other words, who really owns the statistics? Who is primarily responsible for the acquired firm’s present financial status? Who has taken up the slack for whom?

A Race with Only One Runner ...

Related Articles

M&A Integration Management

M&A integrations always require you to make sacrifices. It’s a time of tradeoffs. Compromises. Less than perfect solutions. So far as the people issues are concerned, it’s like watching a card game—some win, some lose, some break even.

You can care deeply—for everybody—but you can’t keep from damaging some careers.

Deep inside, managers know this is the case. Obviously, everybody can’t come out on top. But when it comes down to deciding how the two work forces will actually be integrated, the people calling the shots usually feel compelled to make a show of fairness. Instinctively, they want to come across as acting equitably, to be seen as even-handed in the way they assign people to the various positions.

This sort of behavior is fully understandable. But as it turns out, it’s not particularly good post-merger integration management.

In fact, if being “fair” to current employees is a top priority, merging is probably a bad plan. It’s sort of like wrestling with the decision of whether or not to declare war. How can you justify it if you’re unwilling to sacrifice some lives? Nobody ever said that mergers are the kinder and gentler way to corporate growth.

All too often the attempt to be fair and equitable in the integration process produces bad business decisions. You’ll see it at the very outset, where people are being tapped to serve on the various merger task forces and transition teams. Companies will bend over backward to get equal representation from both organizations. Balance is the big word. And it sells, because it suggests that people on both sides of the fence will have equal say-so on merger matters.

But should they? Usually not.

This approach emphasizes fairness at the expense of competence. And it’s a flawed methodology because it implies that in the future, equal treatment is going to be the norm ...

Related Articles

Employee Turnover in M&A

Organizations have a hard enough time hanging on to good talent these days. Careers have become more a collection of assignments than a collection of seniority pins and gold watches. Work has come to be seen as more an activity than a place. Because of this, the feeling of company belonging and loyalty is a rarer experience than when 20-year stints at the patriarchal corporation were the norm. Introduce a destabilizing event like a merger or acquisition into the picture, and the precarious ties holding employees in their current jobs begin to loosen even further.

The nature of today's deals makes this erosion of loyalty still more of an issue. So many of today’s mergers and acquisitions are not really based on the idea of purchasing hard assets such as plants and equipment. Due to the growth of the service industry, the de-emphasis of leveraged buyouts, and the increase in the value of knowledge, a large percentage of today's purchases and consolidations represent a pursuit of “soft assets.” These soft assets represent the knowledge of the workforce in the target company—for example, the value of patents, relationships with clients, and the opportunities that lie ahead because of the expertise surrounding new products and services under development. Many of today's deals are attractive financial propositions solely because of the knowledge of the people in the company being acquired.

What can be done to protect the investment in this sort of merger or acquisition? One key answer is to conduct a rapid, well-organized, and persuasive re-recruitment effort aimed at the key talent you want to retain.

Why People Leave

It is not surprising that people often choose to leave an organization or "de-commit" during a merger or acquisition. The widespread turmoil created by change turns people's thoughts inward, away from their job and toward personal concerns. Self-protective thoughts swirl through their minds, leaving people to wonder about the wisdom in waiting to see what will happen to their careers.

For the time being, the big concerns people are wrestling with reflect their uncertainty about how they will fare in the new scheme of things. For example, they worry, “What will happen to my job, my pay, my security?” These doubts and unanswered questions create a great feeding ground for headhunters and company recruiters, who naturally step up their efforts to pick off the best talent. These recruiters who are circling the merger scene have the advantage of being able to buzz in fast and lay a hard offer in front of a person. This immediately provides the individual with an alternative to the ambiguity, uncertainty, and personal concerns he or she is experiencing.

The turnover statistics associated with mergers and acquisitions are staggering. Based on our data, when no coordinated retention actions are taken, 47 percent of all senior managers in an acquired firm leave within the first year of the acquisition. But the exodus doesn't stop there. Within the first three years, 72 percent end up heading for the door.

The costs associated with a talent drain of these proportions are enormous. Perhaps equally damaging and just as costly, though, are those people who a stay on the payroll but don't perform. They don’t leave the company physically, but they emotionally check out. No longer feeling any true commitment to their jobs or to the organization at large, these people frequently join the ranks of the critics and are resistive throughout the entire integration process. In this instance, the organization ends up paying people to cause problems.

Remember the first word in [me]rger is me.

Re-recruitment

One of the main challenges of the merger process is the retention and revitalization of the valuable human capital that is in place. This calls for a comprehensive and well-planned re-recruitment strategy that proceeds with a strong sense of urgency.

Three actions are particularly important in carrying out this strategy. First, key people or groups must be identified. Second, it is important to achieve an understanding of their primary motivators. Finally, an action plan designed to address their motivators must be developed and implemented. Such an approach should be executed with all the focus and energy that is normally invested in finding new talent for an organization. In a sense, that is exactly what is going on here: a concentrated effort to persuade people and demonstrate to them that they should join the “new” organization.

Target the Key Talent

Earlier chapters describe in detail a systematic process for evaluating personnel. That recommended approach—or some variation of it—can identify the key people or groups whose loss would have a detrimental impact on the success of the business. Depending on the situation, people can be considered important for various reasons. For the purposes of this re-recruitment initiative, however, the “screen” to use in identifying your target personnel will be the consideration of whatever negative impact would come from losing them. To proceed, then, make a list of the various people or groups, and then determine how their leaving might damage the business. Would their departure also likely mean the loss of a key client or customer? Would it mean the loss of critical technical skills, or maybe knowledge of a core product or service offering? When the answer indicates that losing a particular person would hurt, that individual should be considered a primary target for re-recruitment.

Many organizations have a documented succession plan that identifies the actions that would be taken to fill positions vacated by critical personnel. Although these plans are reactive in nature, they can serve as an excellent check to make sure that all the key people in the organization have been identified for re-recruitment efforts. The re-recruitment plan most likely will include everyone who is on the succession plan list, as well as additional people or groups.

Understand Their Motivators

Knowing what motivates a particular executive or employee is essential for effective re-recruitment. People vary greatly in terms of their personal needs, likes, and dislikes. Obviously, motivating angles can come from avoiding the dislikes as much as from addressing appetites.

The following are the items that might be important to people:

-

Security. Based on the knowledge that one’s job and career path have not been negatively affected by the merger.

-

Feeling “in.” A feeling of importance generated by allowing people to have input to, and knowledge of, decisions before they are widely announced.

-

Control. At a time when feeling in control is uncommon, giving people options can make them feel valued as well as less vulnerable.

-

Ego items. Those things that feed the ego and make one feel special are important to even the most pragmatic business people.

-

Opportunity to “do the right thing.” Helping people understand the reasoning behind merger initiatives—sharing the “why”—appeals to people by helping them feel they are supporting the right approach.

The keener the insights into the individual, the better aimed your re-recruitment efforts can be. It is not necessarily the most expensive or most flamboyant motivator that gives you the most mileage in your efforts to retain someone.

Above all, remember that it's a mistake to attribute to others your personal values or priorities regarding which motivators should count the most. The thing that would guarantee your willingness to stay on board might do nothing at all to keep the next person from leaving the organization.

Security

When people think of organizational change, they often think of potential job loss. Job security, then, becomes a very basic issue to be reckoned with at all levels of an organization that is being acquired or merged. Obviously, the issue of job security needs to be addressed as promptly as possible for those employees who have been identified as critical to the company’s future. Explain to them individually that they are each seen as someone who will play an important role and, as a result, will be kept in the organization. This communication should occur in private, and the message should be delivered in person. Acknowledge that the environment is uncertain at this early stage, and that there are many unknowns. But emphasize to these people that they are an integral part of making the changes work.

The second major aspect of security concerns financial matters. People will have all kinds of questions about their pay and benefits. Because money is such a fundamental concern in the minds of most people, re-recruitment can be a tough drill if you are not in a position to answer the dollar-related questions. The best situation, of course, is to be able to use pay raises, incentive contracts, and performance bonuses as part of the re-recruitment effort. But you often need to be re-recruiting before policies have been hammered out on compensation. In that case, consider “stay bonuses” as an interim means of assuring that the key people have the financial safety necessary to feel good about staying with the organization.

Feeling "In"

A basic need of people working in organizations is to feel “in” on things. They want to know what’s going on. So one of the best ways to maintain the loyalty of key people during times of change is to keep them in the loop.

This can be accomplished in various ways, such as involving them in important meetings or sharing key information with them on a regular basis. Keep them posted about the alternatives being considered. Ask for their input. If these individuals are considered good enough to re-recruit, often they are good enough to help make the difficult decisions.

Some managers make the mistake of presuming they don’t need to share information since no decisions have been made. But people feel more valued and more connected to the organization if they are kept informed.

Control

Over time, managers and executives develop a certain addiction to control. They want to enjoy a generous amount of influence over how things are handled. Many executives, in fact, develop a strong sense of self-worth relative to their span of control. During the merger-integration process, you can appeal to this need by leaving some decisions to them.

While it's true they might not handle things exactly the same way you would, there can be real benefits in allowing them to make the call. Granted, it may be necessary to set some boundaries around the decision-making process or to stress the need for communications about the decisions they're making. Beyond that, however, providing them latitude to make meaningful decisions can be a powerful motivator. This is particularly so in the merger/acquisition environment, where so many people in the management ranks are concerned about how they will be affected by the inevitable shakeup in the power balance.

Remember, too, that the effect of criticism is magnified during the transition period. Don’t be too quick to criticize people for what looks like a bad decision.

To the extent possible, reward people for acting quickly or taking accountability for making things happen. Then, as necessary, provide advice regarding how the decision could be made even more effectively the next time around.

Apart from satisfying managers’ and executives’ need for control, giving them decision-making latitude can help accelerate the integration process.

They demonstrate more ownership of the desired changes, and show more initiative in the implementation of these changes.

Ego

Employee and management “work egos” operate on the belief that “I play an important role in the success of the organization.” This belief gets fueled by a variety of things: a favorable self-concept, positive feedback from others, clear evidence of successful performance, and the status symbols provided to people in organizations. Ego plays a powerful role in how people feel about their employment. And in the merger/acquisition scheme of things—where trust is low, self-protective behavior is rampant, and so many people feel vulnerable—the egos belonging to high-talent personnel often get a little shaky.

Bruised egos cause many of the bailouts. Sometimes the people in question feel threatened. In other cases, people with high need for attention and approval leave because they are being romanced by recruiters, and more or less ignored by their own superiors. While it overstates the case, a guideline to go by is that high performers have developed a larger-than-average appetite for ego gratification. So a person’s ego serves as a promising avenue for re-recruitment.

This argues for getting close to your good people. For making them feel special. The more they feel valued and important to the corporate cause, the better the chances that their job commitment will remain high and they will think in terms of staying with the organization.

Sometimes a big ego boost comes from giving this sort of person a key role, maybe an important assignment in the merger-integration process itself. And typically the ego gets pumped up if a person gets a better title or new perks that normally go with high rank or reputation.

Status symbols may come in the form of administrative assistants, larger offices, first-class travel, or bigger budgets. At management and employee levels, the symbols are perhaps smaller in scope or importance, but they are just as powerful in terms of how they feed people’s work egos. Awards banquets, getting one's name printed in the company newspaper as a high achiever, and trips for reaching major goals all provide an ego boost.

But consider what happens so commonly in a merger. Imagine a $200 million company where executives, managers, and employees are operating a successful, profitable, growing business. Depending on their level in the organization, they can make decisions, allocate capital, respond to customers, set policy, and count on being paid for performance. Then, without much warning, their company is acquired. Soon they find themselves operating as a small, fairly insignificant division of a $12 billion conglomerate. Egos take a hit all across the organization, from top to bottom, and it is a hard thing for people to swallow. They now must abide by new rules and policies set by someone else. Their pay for performance gets replaced with a standard scale set by the acquiring company. Their budgets are cut. They see their latitude to make decisions and respond to customers impeded by a new level of oversight on the part of the acquirer. And the bigger the ego, the harder the hit.

Quick repair of key people’s egos helps greatly in the re-recruitment of the organization’s most important human capital.

Simple actions—timely taken—counter the feelings of losing status that often are associated with change. For example, key individuals might be flown to corporate headquarters to meet with parent company management. They might be given a little better office accommodations or better equipment to work with. Something as simple as a special dinner with senior management in the acquiring organization, or one-on-one meetings to discuss their career opportunities in the new organization, could be just the thing to salve the ego of someone on the verge of seeking a career opportunity elsewhere.

Doing the Right Thing

Whether it is in service of their career, family, or employees, people generally want to do what's right.

The difficulty arises, however, when what seems right for one party is potentially not right for another. When organizations are involved in a merger/acquisition event, key personnel are ordinarily introduced to a new set of stakeholders: investors, analysts, new customers, employees, and others outside the company. During those times of change, the question is not only, “Are we doing the right things?” but also, “Who are we doing the right things for?” Resolving these questions is of paramount importance in making a merger successful. This is especially true in terms of how key people feel about the decisions being made in the change process. The answers heavily influence whether or not people will choose to commit themselves to helping with the integration effort.

It helps, as discussed earlier, to provide people with some sense of control. That gives them more of a feeling that the changes are the right thing to do because they, personally, have some say in them. But most of the time it is not practical, or perhaps even possible, to involve all of the key people in the decisions being made. In those situations where key people are unable to play an active part, the reasoning behind the decisions needs to be made clear. If people have a good sense of the rationale for change, they are better equipped to deal with the second question posed above, “Who are we doing the right things for?”

Obviously, some of the merger-related decisions are not based directly on what is right for specific personnel in the company, but what is right for customers, shareholders, or overall company profitability. Still, doing what is right for the customers or the shareholder or profitability in general should have a positive impact on company personnel—at least in the long term, global sense. This impact commonly comes in the form of higher sales, greater market share, or better margins. And that translates into better chances for pay raises and promotions. Giving people this rationale for the decisions that are made probably won’t make everyone happy. The idea, though, is to help them understand that staying on board and committing to making the changes successful is the right thing to do.

Turn the Motivators into Re-recruitment Actions

Once people’s primary motivators are understood, they should be turned into action steps that correspond with re-recruiting specific individuals and groups throughout the organization. This should be organized as a formal plan—written down on paper—and truly should be actionable.

A well-crafted re-recruitment program will include measurement of how effective the effort has been. Many organizations already measure turnover rates on an annual basis. But in times of change, when re-recruitment becomes extremely important, measuring overall turnover in this manner is not sufficient. Time frames for turnover measurements need to be shortened.

For instance, turnover can be measured on a monthly basis. Historical turnover also should be converted to the same time basis so an accurate comparison can be made between historical and current retention statistics. The rate at which people are leaving also should be tracked in a way that allows trouble spots among specific groups to be spotted early. For instance, turnover measurements might be broken down by rank or hierarchy, geographical location, work group or functional area, and so on.

In addition to tracking turnover, exit interviews should be performed with anyone who announces his or her departure. Because the merger environment accelerates the timeframe in which information needs to be gathered, it is probably wise to conduct these exit interviews before the person’s actual last working day. Regardless of when they are conducted, though, exit interviews can be a valuable tool for gaining insights that strengthen subsequent re-recruitment efforts.

It takes time to develop and execute a compelling re-recruitment strategy, and there are many competing demands for people’s time. Far too often, there is virtually nothing done by way of deliberate re-recruitment, except for scattered attempts to hang on to a handful of upper-level executives. Usually, the measures taken to retain key talent are superficial, poorly coordinated, and carried out with a serious lack of urgency. This helps explain why so many merger/acquisition situations are marked by a mass exodus of valuable talent, and why so many mergers end up in the failure statistics.

Related Articles

M&A Onboarding

If the acquired employee workforce is to be integrated — truly merged — then the staging for this consolidation should begin well before the deal is formally closed. Problems develop rapidly when the parent firm fails to orchestrate a prompt and systematic assimilation process.

Organizations routinely suffer a loss of identity upon being acquired and with that loss comes an erosion of employee commitment. Motivation deteriorates as my people's sense of "my company" fades and blurs, making it harder for them to maintain an emotional attachment to the organization. Also, personal ties to upper-level managers or the owner may be severed as those people leave the scene, eliminating important personal loyalties that previously generated strong motivational forces. Other demotivating merger factors include stress, uncertainty, feelings of loss, and fear of change. The best antidote for these ailments is powerful onboarding.

Of course, there are some companies (the old Beatrice Foods is a good example) whose acquisition philosophy did little to destabilize or threaten corporate identity. As Beatrice bought out such firms as Samsonite, Stiffel, La Choy, and Gebhardt, most employees were never personally affected by the change in corporate ownership. Beatrice made a deliberate effort to let acquisitions keep their individuality and the same management team. Each stand-alone subsidiary continued to use its own name and company colors. There was no real integration, and the less apparent it was that the company had been bought, the better.

When an acquisition will be integrated and its current corporate identity reshaped, the parent (or surviving) firm has an obligation to bring acquired employees into the fold. This calls for comprehensive, sustained onboarding. People in the acquired firm need to develop a feeling of citizenship in the new corporate structure. They need guidance on what to expect and how to fit in. They need help in making social connections that can provide a new sense of belonging.

Yes, it takes time and money, but the return on investment is huge. Acquirers that skimp in their onboarding efforts pay a far heavier price in the long run as they wrestle with integration problems which easily could have been prevented.

Four Key Benefits of Onboarding

A well-crafted onboarding program can be your best counter-offensive against the chronic and troublesome merger dynamics of ambiguity, a weakened trust level, and self-preservation behavior. In particular, onboarding can make major contributions in four critical areas:

- Retention of talent—A robust onboarding process will mobilize a carefully targeted recruitment activity designed to identify flight risks, reduce the fear and uncertainty, ensure that key players feel valued, and cast the newly merged company in a favorable light.

- Rapid engagement—The mechanics of a comprehensive onboarding program can minimize resistance to change, facilitate bonding with the new organization, plus redirect energy away from anxiety and toward the job at hand.

- Accelerated productivity—Onboarding provides role clarity, valuable connectivity with new coworkers, necessary new skill development, plus a sharper understanding of the merged organization's strategy and business plans. This enhances job commitment and personal effectiveness.

- Cultural alignment—Socialization and acculturation activities aid assimilation by helping acquired personnel crack the code of the parent company's culture. This helps people know how to align with and adapt to new ways of working.

Onboarding should be a key component of your change management efforts during the integration process.

Common Onboarding Problems: Too Late... Too Little... Too Poorly Executed

Research shows that onboarding should start sooner and continue longer than it does in most mergers.

For example, activities designed to facilitate assimilation and cultural alignment usually could begin during the period between announcement of the deal and the close date (or "Day 1"). Sometimes these so-called "preboarding" initiatives are the most constructive of all, serving as a positive launch pad for integration and preempting some of the most common merger problems. But many merging organizations fail to initiate any onboarding work during this early time frame. The result, naturally, is that merger problems get a head start on management.

Most companies also shut down their onboarding efforts much too soon. If they do any formal onboarding at all, they quit before finishing. A benchmark report on best practices found that 86 percent of some 800 organizations surveyed globally agree that it takes as much as six months for new employees to make a firm decision to stay. However, 61 per cent of those same organizations either (a) don’t provide a formal onboarding program or (b) end their program within just one month. This is just asking for trouble in the integration process. It's virtually impossible for acquired personnel to blend in culturally, develop a sense of belonging, or be comfortable with new work processes and practices in a month or less.

Employees who are being acquired and merged feel vulnerable. They hunger for information, for guidelines and answers, for anything that can reduce the uncertainty and help them navigate through the merger transition period more safely. Given their apprehension, the onboarding process should be empathic, supportive, and welcoming. But frequently these people feel that they're being treated like stepchildren.

Of course, practically all acquirers will perform at least a few basic, nuts-and-bolts tasks which they could point to as onboarding activities. For example, forms are filled out to get people signed up for payroll, benefits, and such. Work stations are assigned and equipped. There may also be a brief “orientation session” for the newcomers. Too often, though, the parent company provides the acquired workforce little beyond an impersonal Day 1 data dump and a pile of paperwork.

Rather than treat onboarding as a one-time event, think of it as an extended program, a broad spectrum process of transitioning and assimilating people into meaningful citizenship, cultural alignment, and operational effectiveness in the new organizational scheme of things. That takes time.

Three Key Aspects of Strategic Onboarding

Administrative tasks are the quickest, easiest, and most common aspect of the onboarding process. First, they involve basic forms management—the paperwork, documentation, or red tape involved in establishing personnel files and getting acquired employees into the record-keeping system. Other administrative steps involve equipping these people with the physical gear they need to do their work, such as a desk, phone, computer, voicemail and email, keys or access cards, employee handbook, phone directory, etc.

The second aspect of onboarding centers on managerial tasks. Here things become more intangible and ambiguous, more behavioral in nature, and much more dependent on effective communication. The focus is on defining the acquired employees’ work roles, responsibilities, and performance expectations. Management also needs to familiarize newcomers with the relevant company processes, practices, and performance management criteria. This may involve training, coaching, or shadowing a veteran employee to help these people get up to speed on the job.

The third, and by far the most complex, aspect of onboarding deals with socialization and cultural alignment. The acquired workforce should be given a sense of the parent company’s history and indoctrinated with its values, norms, and corporate philosophy. Naturally, this needs to be done in such a way that it does not offend. It should not come across as propaganda or look like an attempt to brainwash, but instead represent an honest and humble effort to communicate the new corporate culture and help newcomers adapt. This aspect of onboarding also seeks to help people through the social transition as they merge into new work groups. Socialization tactics might include a buddy system, mentoring programs, orientation sessions, mixers, Q8A meetings with senior executives, peer networking, or training programs on culture and organizational change.

Create an Onboarding Roadmap

The overall design and general timetable for an onboarding program can be mapped out well in advance. In fact, you can sketch it out in broad terms even before a deal is on the table. This framework then can be fine-tuned to fit the specific details of any given merger/acquisition.

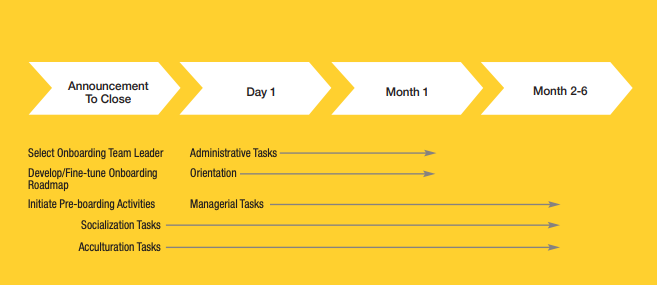

The following four-stage onboarding model depicts the focus of work along a typical integration pathway.

The program should be carefully choreographed and set up as an independent, cross-functional work stream under the oversight of the Integration Management Office. The onboarding team leader, reporting to the Integration Manager, should have single-point accountability with the decision authority to manage and coordinate the full implementation of the onboarding process.

Related Articles

Some 200 years ago, Jane Austen—one of Britain’s best-loved authors—wrote a famous novel about marrying. And money. Deep down that’s actually what mergers are about, too, so I thought to myself, “Maybe her classic, Pride and Prejudice, has parallels for merger integration.”

After all, “corporate marriage” is the most common metaphor used when people talk about combining two companies. And as for the part about money, well, M&A is always based on a financial proposition.

Since Austen’s story about 18th century England focuses on social class, let’s look at merger integration from that angle. In the hierarchy of power and status, the Board of Directors is the uppermost class…the top rung of the corporate social ladder…the highest level of governance.

So how do pride and prejudice affect the integration process in boardroom society?

Merging Begins at the Board Level

Actually very little has been written about the wedding of boards when companies marry. This is peculiar, given the importance of directors and the fact that boards are at the front of the line for integration.

Merging is ordinarily a top-down process. Directors go first. They’re the top link in the chain of command, and the makeup of the merger’s new leadership structure needs to be resolved as quickly as possible. Urgency in blending the two boards into one means this elite crowd will be among the first to feel three highly predictable dynamics triggered by a merger:

- A sharp increase in ambiguity and uncertainty

- A drop in the trust level

- Arousal of instincts for self-preservation

These are natural human responses. When change hits, the first scan is for danger. And as the playwright John Dryden stated, “Self-preservation is Nature’s oldest law.”

We can hope that directors will be selfless and statesmanlike as the board gets reconfigured, but let’s not presume that they are Vulcans. These power brokers fall prey to the very same “me issues” that will bedevil the entire workforce as the integration process unfolds. Incumbent board members wonder, “Will I get to keep my directorship? How might my role on the board change? What will happen to my compensation?” And so on.

These concerns make perfect sense. Since board personnel are the first batch of people facing consolidation in the merger, some will be the first victims of redundancy.

Pride Cometh

Integration is a politically sensitive process at all levels of an organization, but especially so in the rarified air of the boardroom. Pride is more easily bruised at this altitude.

After all, directorships are a badge of honor—ego gratifying, high octane fuel for one’s self-esteem. People who occupy these positions often covet the prestige more than any monetary rewards that come with a board appointment. Some find that the power carries the most appeal. Some put more value on the business connections that come with the job. Some prize most the upper crust coolness of being in a network of celebrity names.

Of course, there are other perhaps more noble psychic rewards, such as the intellectual challenge, an opportunity to contribute, or a chance to learn and broaden one’s self through board work. But regardless of how directors weigh the rewards as individuals, those who lose out in the board shakeup get their egos banged up a bit in the process.

So, does this matter? Why worry about someone’s potential for injured pride? Well, as folk wisdom says, “Wounded animals are dangerous.”

Merging Creates a More Complicated Agenda

At the very time directors naturally become more self-oriented, their workload becomes more complex. This is a particularly troubling situation because board effectiveness needs to be at its peak.

Let’s consider the new hazards.

First, merging introduces a fresh set of risk factors, a more vulnerable time for the business. Also the board’s workload ratchets up and intensifies. Priorities shift. The company comes under much sharper scrutiny by shareholders and the media. The competition circles, trying to take advantage of the situation. Directors must address a broad range of heavy-duty considerations regarding strategy, culture, operating style, financial pressures, etc.

Meanwhile, the board itself is being reconfigured, which causes distraction and a regression in teamwork. The crossbreeding process in merging the two boards involves new assignments for directors, changes in the pecking order, and adjustments to new personalities.

Trust is the grease that lubricates directors’ ability to guide and govern the new combined entity through the hazards of merger integration. But the trust level in the boardroom dips sharply in the face of these assimilation challenges.

The Clint Eastwood Observation

The movie star and former mayor of Carmel points out the danger here in his remark:

“The less secure a man is, the more likely he is to have extreme prejudice.”

Taking that statement to heart, we should expect that directors will become more influenced by their personal biases as dealmakers finalize the merger. And it’s reasonable to believe their thinking will rely more heavily on preconceived notions.

Obviously, as Eastwood suggests, this dilemma of slanted mindset can hijack directors’ objectivity. The natural result? More prejudicial problem-solving and decision-making threads its way into boardroom behavior. There’s an impulse to think, “Our company’s way is better”…”Our people are more capable”…”Our sense of what should happen is best.”

Ordinarily, these are honest points of view, even as they can be entirely wrong. Directors may be struggling to be fair minded and dispassionate. They might wish to analyze circumstances from a position of neutrality and probably would argue that they do. But such an intention and desire hardly guarantee success. Human behavior is what it is, the psychology of self-defense runs deep, and our prejudices deceive us all too easily.

Protecting the Board from Human Nature

There are, however, practical steps that can defend the board of directors against the political effects of pride and prejudice. Let’s keep it simple here, focusing on what I’ll call the minimum effective dose (MED) for dealing with board transitions during a merger.

MED is defined as the smallest dose that will produce a desired outcome. The MED not only delivers the most dramatic results, but it does so in the least time possible. Certainly more can be done, but more is not necessarily better—often greater dosages are wasteful. Maybe damaging.

Here are three of the most constructive moves you can make:

-

Bring outsiders onto the board right out of the gate. This means you need to leave some seats open, rather than stack the new board full of legacy directors from the two organizations.

It may seem counterintuitive, but odds are your newly configured board will coalesce quicker and be more effective with brand new directors in the mix.

-

Disregard the urge for pro rata board representation. You might feel pressure to allot directorships on a proportional basis, but board seats should not be dictated by the respective sizes of the two merging firms.

For example, companies of near equal size often feel obligated to go 50-50, following that seemingly equitable practice of giving half of the directorships to each company. But look at it this way—if you were merging the Pittsburgh Steelers with the Dallas Cowboys, would it ever enter your mind to insist that half of your new offensive and defensive teams had to come from each organization? Not a chance. You’d go for talent, not for surface appearances. And you wouldn’t compromise the new team’s future by making some feeble attempt at parity for purely political reasons.

Look—merging offers a prime opportunity to strengthen your board. Seize the moment. Use the shakeup to replace weaker directors. Your new slate of board members immediately faces greater challenges and must govern the company at its suddenly enlarged level. Presumably, the merger created a stronger business. Does it not deserve a stronger board?

-

Use an expert board facilitator, an outside consultant, to advise and guide the board into the transition. Such a person, with deep knowhow and no axe to grind, can make a huge contribution in the merging process at this highest level of governance.

This professional can immediately improve the board’s ability to—

- Make decisions as a group

- Be a unified voice

- Operate with role clarity

- Work through philosophical divides

Assuming that you adhere to these minimalistic guidelines, will merging two boards into one remain a sensitive, highly political process? Absolutely. That’s the nature of the beast. But these three practices alone go a long way toward positioning your new director group for merger success.

What Counts Most is How the Story Ends

Pride and Prejudice, like other Jane Austen books, has a happy ending. The main characters overcome their personal struggles and love wins out. The marriage works.

But a large percentage of corporate weddings end badly. While the reasons vary, many of these merger disappointments could be avoided through better governance by the board of directors. Remember—that’s where the integration process begins.

Having been involved in M&A now for some 40 years, I know the habits of CEOs and board chairmen. And the fact is they’re disinclined to follow the minimum effective dose prescription outlined above. To be honest, I understand why. The politics of integration are delicate indeed.

Here’s the irony: While it’s quite rare for merging boards to take the three steps that are recommended, it’s remarkably common for them to say they wish they had.