M&A Onboarding

If the acquired employee workforce is to be integrated — truly merged — then the staging for this consolidation should begin well before the deal is formally closed. Problems develop rapidly when the parent firm fails to orchestrate a prompt and systematic assimilation process.

Organizations routinely suffer a loss of identity upon being acquired and with that loss comes an erosion of employee commitment. Motivation deteriorates as my people's sense of "my company" fades and blurs, making it harder for them to maintain an emotional attachment to the organization. Also, personal ties to upper-level managers or the owner may be severed as those people leave the scene, eliminating important personal loyalties that previously generated strong motivational forces. Other demotivating merger factors include stress, uncertainty, feelings of loss, and fear of change. The best antidote for these ailments is powerful onboarding.

Of course, there are some companies (the old Beatrice Foods is a good example) whose acquisition philosophy did little to destabilize or threaten corporate identity. As Beatrice bought out such firms as Samsonite, Stiffel, La Choy, and Gebhardt, most employees were never personally affected by the change in corporate ownership. Beatrice made a deliberate effort to let acquisitions keep their individuality and the same management team. Each stand-alone subsidiary continued to use its own name and company colors. There was no real integration, and the less apparent it was that the company had been bought, the better.

When an acquisition will be integrated and its current corporate identity reshaped, the parent (or surviving) firm has an obligation to bring acquired employees into the fold. This calls for comprehensive, sustained onboarding. People in the acquired firm need to develop a feeling of citizenship in the new corporate structure. They need guidance on what to expect and how to fit in. They need help in making social connections that can provide a new sense of belonging.

Yes, it takes time and money, but the return on investment is huge. Acquirers that skimp in their onboarding efforts pay a far heavier price in the long run as they wrestle with integration problems which easily could have been prevented.

Four Key Benefits of Onboarding

A well-crafted onboarding program can be your best counter-offensive against the chronic and troublesome merger dynamics of ambiguity, a weakened trust level, and self-preservation behavior. In particular, onboarding can make major contributions in four critical areas:

- Retention of talent—A robust onboarding process will mobilize a carefully targeted recruitment activity designed to identify flight risks, reduce the fear and uncertainty, ensure that key players feel valued, and cast the newly merged company in a favorable light.

- Rapid engagement—The mechanics of a comprehensive onboarding program can minimize resistance to change, facilitate bonding with the new organization, plus redirect energy away from anxiety and toward the job at hand.

- Accelerated productivity—Onboarding provides role clarity, valuable connectivity with new coworkers, necessary new skill development, plus a sharper understanding of the merged organization's strategy and business plans. This enhances job commitment and personal effectiveness.

- Cultural alignment—Socialization and acculturation activities aid assimilation by helping acquired personnel crack the code of the parent company's culture. This helps people know how to align with and adapt to new ways of working.

Onboarding should be a key component of your change management efforts during the integration process.

Common Onboarding Problems: Too Late... Too Little... Too Poorly Executed

Research shows that onboarding should start sooner and continue longer than it does in most mergers.

For example, activities designed to facilitate assimilation and cultural alignment usually could begin during the period between announcement of the deal and the close date (or "Day 1"). Sometimes these so-called "preboarding" initiatives are the most constructive of all, serving as a positive launch pad for integration and preempting some of the most common merger problems. But many merging organizations fail to initiate any onboarding work during this early time frame. The result, naturally, is that merger problems get a head start on management.

Most companies also shut down their onboarding efforts much too soon. If they do any formal onboarding at all, they quit before finishing. A benchmark report on best practices found that 86 percent of some 800 organizations surveyed globally agree that it takes as much as six months for new employees to make a firm decision to stay. However, 61 per cent of those same organizations either (a) don’t provide a formal onboarding program or (b) end their program within just one month. This is just asking for trouble in the integration process. It's virtually impossible for acquired personnel to blend in culturally, develop a sense of belonging, or be comfortable with new work processes and practices in a month or less.

Employees who are being acquired and merged feel vulnerable. They hunger for information, for guidelines and answers, for anything that can reduce the uncertainty and help them navigate through the merger transition period more safely. Given their apprehension, the onboarding process should be empathic, supportive, and welcoming. But frequently these people feel that they're being treated like stepchildren.

Of course, practically all acquirers will perform at least a few basic, nuts-and-bolts tasks which they could point to as onboarding activities. For example, forms are filled out to get people signed up for payroll, benefits, and such. Work stations are assigned and equipped. There may also be a brief “orientation session” for the newcomers. Too often, though, the parent company provides the acquired workforce little beyond an impersonal Day 1 data dump and a pile of paperwork.

Rather than treat onboarding as a one-time event, think of it as an extended program, a broad spectrum process of transitioning and assimilating people into meaningful citizenship, cultural alignment, and operational effectiveness in the new organizational scheme of things. That takes time.

Three Key Aspects of Strategic Onboarding

Administrative tasks are the quickest, easiest, and most common aspect of the onboarding process. First, they involve basic forms management—the paperwork, documentation, or red tape involved in establishing personnel files and getting acquired employees into the record-keeping system. Other administrative steps involve equipping these people with the physical gear they need to do their work, such as a desk, phone, computer, voicemail and email, keys or access cards, employee handbook, phone directory, etc.

The second aspect of onboarding centers on managerial tasks. Here things become more intangible and ambiguous, more behavioral in nature, and much more dependent on effective communication. The focus is on defining the acquired employees’ work roles, responsibilities, and performance expectations. Management also needs to familiarize newcomers with the relevant company processes, practices, and performance management criteria. This may involve training, coaching, or shadowing a veteran employee to help these people get up to speed on the job.

The third, and by far the most complex, aspect of onboarding deals with socialization and cultural alignment. The acquired workforce should be given a sense of the parent company’s history and indoctrinated with its values, norms, and corporate philosophy. Naturally, this needs to be done in such a way that it does not offend. It should not come across as propaganda or look like an attempt to brainwash, but instead represent an honest and humble effort to communicate the new corporate culture and help newcomers adapt. This aspect of onboarding also seeks to help people through the social transition as they merge into new work groups. Socialization tactics might include a buddy system, mentoring programs, orientation sessions, mixers, Q8A meetings with senior executives, peer networking, or training programs on culture and organizational change.

Create an Onboarding Roadmap

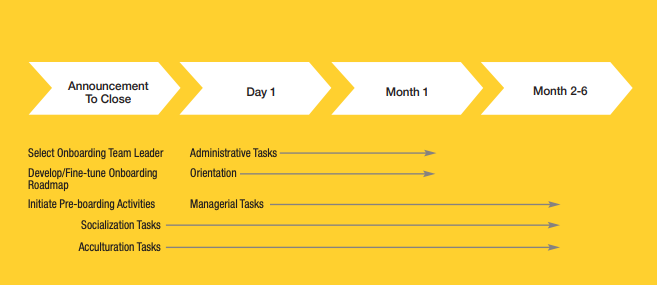

The overall design and general timetable for an onboarding program can be mapped out well in advance. In fact, you can sketch it out in broad terms even before a deal is on the table. This framework then can be fine-tuned to fit the specific details of any given merger/acquisition.

The following four-stage onboarding model depicts the focus of work along a typical integration pathway.

The program should be carefully choreographed and set up as an independent, cross-functional work stream under the oversight of the Integration Management Office. The onboarding team leader, reporting to the Integration Manager, should have single-point accountability with the decision authority to manage and coordinate the full implementation of the onboarding process.