AFTER the MERGER

IntroductionTHIRD EDITION

After the Merger is the first book ever published on merger integration strategy. Library Journal named it “One of the Ten Best Business Books of the Year” in 1985. Now a classic, it has remained in print and enjoyed steady sales for more than a quarter of a century, evidence that the book’s insights and advice are sound enough to endure the test of time.

Why the continuing popularity? Two reasons.

- After the Merger describes the integration landscape with clarity.

- It focuses on the few critical concepts that hold the key to successful integration.

Often a book’s guidelines become outdated with the passing years, but the message in After the Merger remains just as true and useful today as when it was first written. Why? Three reasons.

- The organizational dynamics of merger integration haven’t changed.

- The core management challenges inherent in M&A haven’t changed.

- The basic principles for effective integration haven’t changed.

This is a book about fundamentals, and that’s why it lives on.

Every deal is different . . . but every deal is also alike. Human nature is the constant—people are people—and mixing two organizations together produces a very predictable set of behaviors. If you know that pattern, and if you understand the problems it causes, then you’re positioned to manage the integration effectively.

It’s a bit ironic—today’s mergers and acquisitions encounter the very challenges companies have faced for decades. Same old same old.

Just wait. Case studies yet to be written about this year’s mergers will report integration problems that parallel those of years past.

After the Merger spells out how to deal with these predictables. It tells you what to expect, why things happen as they do, and how to manage the situation such that your merger has a happy ending.

IntroductionFIRST EDITION

Mergers and acquisitions serve as one form of corporate growth, and it’s worth remembering that growth, whether in an individual or an organization, frequently brings with it some discomfort as well as some awkward behavior. How can executives and managers best handle these growing pains? What can be done to overcome the adolescent clumsiness that comes from newly developed corporate muscle not yet matched by coordination?

The best steps probably are preventive ones. But because of the nature of acquisitions—how the deals are pursued, negotiated, and finally struck—many problems cannot be preempted. They can only be anticipated, met head-on, and dealt with in a professional and timely manner.

Certainly one of the things top management can do is be prepared for the organizational dissonance that is virtually always one of the upshots of merger/ acquisition activity. The destabilizing force that is generated opens the door for change, for positive effect. It is a motivating force top management can seize to fuel growth and improve performance. It is energy that can be harnessed.

The dissonance must be managed intelligently and carefully channeled, or it can be disastrous. The upheaval is not something to be stifled, sidestepped, or ignored. It should be parlayed into a positive thrust. But only rarely is it fully exploited for its potential benefit to both firms involved.

Often the dissonance—the psychological shock waves—appear to be unexpected, poorly understood, and inadequately governed. As a result, there is much organizational trauma that could have been avoided, and many potential benefits of the destabilization are not seized.

The people responsible for engineering mergers and acquisitions have developed a high degree of expertise in handling the legal and financial aspects of the deal. Regrettably, there is no corresponding sophistication in post-merger management. And regardless of how astute a job the deal makers do, the merger is not going be a bargain if management doesn’t make it work.

So this is a book about managing, rather than making, mergers and acquisitions. The intent is to sharpen managerial insight and understanding into the unique dynamics that characterize this form of corporate development. It is an effort to give direction and straightforward answers to executives and managers who must carry the burden of making the merger measure up to the potential the deal makers originally conceived.

Every year, thousands of acquisitions must be shepherded by new owners and managers. These people need guidelines, plus a frame of reference that makes sense of the problems peculiar to this organizational event.

The symptomatology and underlying problems are remarkably consistent, regardless of the size of the companies being acquired. It may be a megadeal, such as Boeing buying McDonnell Douglas or Hilton attempting a takeover of ITT Sheraton. It may be a foreign acquirer such as British Telecommunications purchasing MCI to get a foothold in the U.S. market. Finally, there are innumerable owner/entrepreneurs who take their life savings and commit to a scary load of personal debt to buy some little business that another individual started but now wants to sell.

Granted, every single merger agreement that is reached will be unique in some respects. But there will be a remarkable number of features they all hold in common—enough that managers and executives can be told what to expect and how to contend with the situation most effectively.

That is the purpose of this book.

Chapter 1

Problems in Buying a "USED" Company

It is lunchtime on a Thursday at the University Club in downtown Chicago. The three businessmen seated at a table near the window are on their last cup of coffee.

One is the CEO of an acquisition-minded pharmaceutical company. Another is the president of a major insurance company that recently bought a financial service firm. The third owns a small manufacturing company, and he is in the process of selling his firm. The lunch crowd is thinning out, but at this table the conversation isn’t lagging.

The pharmaceutical executive leans into the table, eyes the other two, and growls, “It’s a helluva lot like buying a second-hand car. We try to do our homework, but the pre-acquisition analyses never tell us all we need to know about how the outfit has been run. It’s like kicking the tires, looking under the hood, and driving the car around the block. You’re probably going to have a tough time seeing things the seller doesn’t want you to see. Negotiations are the same whether you’re buying a car or a company. That other guy is going to highlight the positives while concealing or downplaying problems. Every company we’ve bought since I became CEO has given us some nasty surprises.”

Nodding and looking out the window across the Chicago skyline, the insurance company president adds, “We’re facing the same problems right now with a company we just acquired. We’re beginning to realize that the previous owner drove the car differently. When he owned the company, it was one-man rule. But we operate in a decentralized fashion, so it’s like the whole family has to know how to drive. The previous owner also pampered the machine, while our management style and philosophy is to drive hard. We’re beginning to wonder if the acquisition will be able to handle the strain. On top of these problems, we have to deal with the negative press coverage we’ve been getting from the business journals. They keep writing that we’re not knowledgeable about how to operate this kind of vehicle, that we don’t have anybody who knows how to drive it. Where we really ran into problems was when we lost some of the seasoned executives we had expected would stay at the wheel, guys that had an outstanding track record.”

The owner of the manufacturing firm grins at his two companions and says, “So I’m supposed to have something in common with the used car salesman? Well, let me play with that for a minute. Sure, I’m selling an organization that needs some repairs. I doubt that the people who are buying me out really know how well my company has been maintained. Furthermore, I don’t know if they are mentally or financially prepared to make the repairs or, in other words, to give the organization what it needs.”

“They plan on doing a minor tune-up, while you’re sitting here knowing it’s really due for a major overhaul, right?” the insurance company president says.

The owner/entrepreneur squints back at the insurance company president and replies, “That’s probably being a little too hard on me. Besides, I get the feeling they’re planning on dismantling the car and selling off some of the parts anyhow.”

The CEO reflects on this for a few moments, then asks, “What happens to the whole when they sell off some of the parts? Is there going to be a breakdown? We tried that approach two years ago, and I guess we must have inadvertently sold the wheels because that acquisition never went anywhere.”

“Well, it’s basically out of my hands,” the manufacturing executive says. “There’s a lot I could have told the guys who are buying me out, but they never asked the right questions. In fact, they haven’t paid much attention to what I did tell them. The word I get from my old employees who are still with the company is that nobody’s listening to them either. So what the hell? God helps those who help themselves.”

As the three men get up from the table to leave, the president of the insurance company remarks, “I guess so.

But whoever said ‘What you don’t know can’t hurt you’ obviously didn’t know beans about mergers and acquisitions.”

Chapter 1

Problems in Buying a "USED" Company

STATISTICS ON MERGER SUCCESS AND FAILURE

Nobody has a very precise set of statistics regarding the success rate for mergers and acquisitions in the United States. One key reason is that, according to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), approximately 60 percent of all merger activity is never publicized or consists of small transactions (less than million-dollar deals) that no one tracks systematically. According to the studies that have been conducted and the merger monitoring that is reported, though, growth through acquisition is a risky business.

Available statistics generally indicate that, on the whole, acquirers have

less than a 5O-5O chance of being successful in merger/acquisition ventures.

Granted, success is a qualitative issue. What looks like success today may subsequently turn out to be a fiasco. And current disappointments can sometimes blossom forth to become outstanding moneymakers. But the grim facts remain—far too many mergers go bad.

Back in the 1980s, Acquisition Horizons studied data on 537 companies that had made at least one acquisition within a five-year time frame. Over 40 percent of the respondents described their acquisition efforts as only somewhat successful or unsuccessful. The most frequently mentioned reason for the disappointing results was that management in the acquired firm was not as strong as expected. Other major reasons were that the preacquisition research proved inadequate or inaccurate, the systems were not as well developed as had been thought, a new strategic plan was needed for the acquired firm, integration planning was not all that it should have been, and finally, some of the key management talent left the firm. The companies studied ranged in size from $125 million to over $2 billion in annual sales.

Another 1980s study conducted by Fortune magazine analyzed 10 major conglomerate acquisitions. All acquisitions represented a move by the parent company into a new line of business, and the question posed by the study was, “Do conglomerate mergers make sense?” At least at the end of the 10-year period when this backward look occurred, they did not.

Michael Porter made an even longer-term measurement, studying the success rate of 33 highly regarded companies over a 36-year period of acquiring. His data revealed that over half of the “unrelated” acquisitions were later divested.

Research by McKinsey & Company found a failure rate of 61 percent in acquisition programs, with failure defined as not earning a sufficient return (cost of capital) on the funds invested. Considering how much hard work and emotional strain are involved in managing mergers and acquisitions, it seems appropriate to say,

so much effort . . . so little return.

The obvious question is “What’s going wrong? Why do the statistics look so bad?” Undoubtedly, all acquirers are well intentioned in their growth plans and fully expect to be successful in the buying and blending of other firms. Some of the failures and disappointments can be legitimately explained away, attributed to something like an unfavorable economic turn of events. Sometimes the acquisition was a mismatch in the first place, with small odds for success. A high percentage of merger difficulties and failures, though, derives directly from faulty management. Target companies are strategically sought and strategically stalked, but then the follow-up acts are poorly orchestrated. The acquirer stumbles along, improvising instead of following a strategically designed, systematically conducted program for corporate integration. Hard to believe, with this much money at stake? A study by the Boston Consulting Group found that, prior to the acquisition, fewer than 20 percent of companies had considered the steps necessary to integrate the acquisition into their organizations.

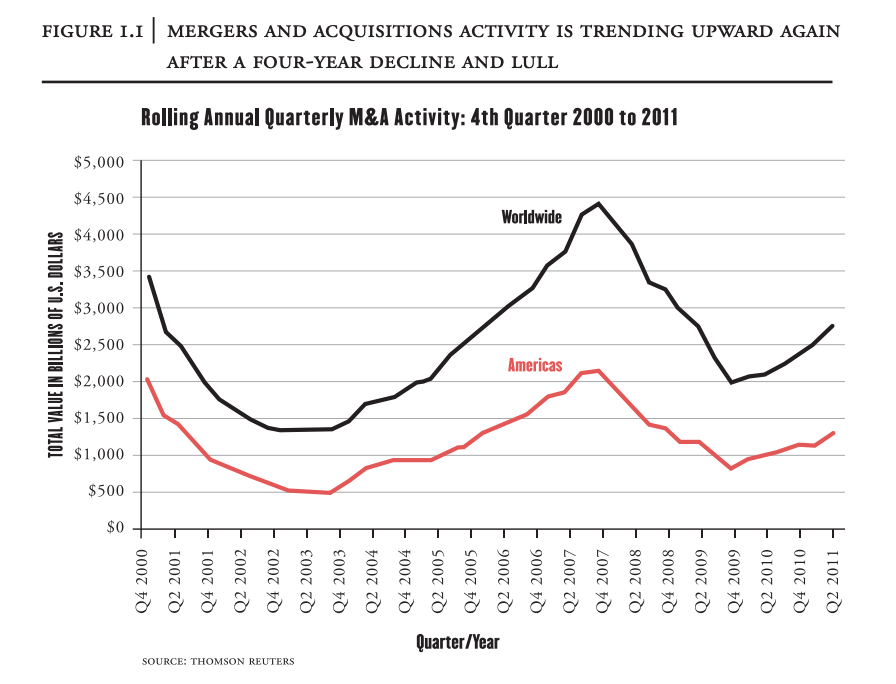

But the beat goes on. The number of failures seems to have no negative effect on the urge to merge. Major economic downturns typically cause a big drop-off in M&A traffic (Figure 1.1), but as soon as markets stabilize dealmakers regain confidence in their ability to make mergers work.

Companies want growth. Their strategies call for mergers and acquisitions, and they’re willing to bet on their ability to beat the odds.

Chapter 1

Problems in Buying a "USED" Company

MERGER/ACQUISITION MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES

Moving into New Territory

Some acquisitions are inherently much more risky than others. The more difficult ones ordinarily represent a move in new directions by the acquirer. And since they are more troublesome, the parent firm should be prepared to invest more time, energy, and money in the integration effort. A well-crafted game plan is essential, one that is structured to deal with the predictable problems of the transition period yet allows the flexibility necessary to accommodate contingency plans that invariably are needed.

Acquisition forays into a different industry or new line of business, for example, should be preceded by integration planning that respects the critical need to hang on to incumbents for the business savvy they possess. One management retention study has found that only one chief executive in ten still occupied the top management job two years after his or her company was acquired.

Way back in 1981, Peter Drucker made the following comment about this risk factor in mergers/acquisitions:

Within a year or so, the acquiring company must be able to provide top management for the company it acquired. It is an elementary fallacy to believe one can “buy” management. The buyer has to be prepared to lose the top incumbents in companies that are bought. Top people are used to being bosses; they don’t want to be “division managers.” If they were owners or part owners, the merger has made them so wealthy they don’t have to stay if they don’t enjoy it. And if they are professional managers without an ownership stake, they usually find another job easily enough.

Drucker then went on to say that, “To recruit new top managers is a gamble that rarely comes off.” A number of years have passed since he made those observations, but his point still holds true.

Often people in both firms will be seriously troubled about how the acquisition may affect their personal careers. Part of the merger/acquisition planning should be aimed at deciding how these concerns will be addressed. By no means do people in the target company have a monopoly on this career uneasiness. After Novell’s ill-fated merger with WordPerfect, for example, people in both organizations experienced dismay. The deal took the combined company to the brink of disaster. And after buying WordPerfect for $855 million, Novell sold it to Corel less than two years later for only $115 million—a loss of nearly three quarters of a billion dollars.

Sometimes the lack of a carefully orchestrated and closely monitored integration effort causes an impending merger to fall apart even before the final papers have been signed. A well-regarded international consulting firm of medium size reached agreement with one of the Big Six accounting firms to merge forces. Even at the outset, though, the prospect of being acquired created serious apprehension throughout the smaller organization. Things got totally out of hand when representatives of the acquirer showed up to do merger data gathering at various regional offices of the consulting firm. People at these sites got the impression they were being audited, and the resulting animosity rapidly became unmanageable. That merger was subsequently called off, but follow-up efforts by the consulting firm to merge with another suitor were complicated by the “merger hangover” resulting from the first episode. The second potential acquirer was itself a subsidiary of a much larger parent company in still another business, and personnel in the consulting firm, still gun-shy about how they had been blitzed by the “auditors,” were leery of any other linkups.

Culture Shock

Corporate culture may be a rather amorphous concept, but its influence is pervasive. Organizations that appear to be highly compatible and that seemingly should be able to achieve valuable merger synergies can have underlying cultures that seriously threaten coexistence.

Corporate culture is a peculiar blend of an organization’s values, traditions, beliefs, and priorities. It is a sociological dimension that shapes management style as well as operating philosophies and practices. It helps determine what sort of behavior is rewarded in an organization, whether the rewards are tangible (salary, bonuses, promotions, perquisites, and so on) or intangible (respect, access to information, power, and so on). An organization’s culture helps establish the norms and unwritten rules that guide employee actions. It legitimizes certain behavior and attitudes while disaffirming others.

In merger scenarios where markedly different cultures collide, employees find that behavior once sanctioned is no longer rewarded, maybe not even approved of, and perhaps may be even punished.

The measuring stick invariably changes and, of course, new people are involved in taking the measurements. Incumbents are put on the defensive as they anticipate a threat to their corporate values and organizational lifestyle. As priorities blur and inconsistencies appear between new approaches and the old way of doing business, culture shock sets in. People first become confused, then frustrated, then resistant to change.

The conventional viewpoint is that the downhill slide of Pan American World Airways, Inc., was precipitated and complicated by its acquisition of National Airlines, Inc., a company with a very different culture. Efforts to blend the workforces met with incredible resistance and bred severe morale problems. Productivity and profitability declined steadily as negative employee attitudes were reflected in weaker job performance and in customer relations problems.

The potential for these problems is compounded when the merger involves international partners. Japan’s invasion of Hollywood began in the late 1980s but was considered a financial disaster by the early 1990s. Sony Corporation and Matsushita Electric Industrial Company bought Columbia/Tristar and MCA, respectively, as a way to leverage their technology in the entertainment industry. Unfortunately the consensus-building cultures of the Japanese companies were not ready for the ego-driven, aggressive, deal-making environment of Hollywood. Rather than continue to invest more money, Sony wrote down over $3 billion of a $6 billion investment, and Matsushita sold MCA to Seagrams.

Some acquirers circumvent problems related to cultural differences by permitting their acquisitions to remain as freestanding operations with only minimal influence or involvement of the parent company. In many situations, however, that approach simply is not feasible. For example, the economies of scale that could be accomplished by merging two organizations may justify the efforts associated with reconciling cultural differences. But in those circumstances, a part of the integration strategy should be aimed at addressing cultural issues.

Sometimes one or both of the organizations involved desperately need a culture change to remain competitive. In that case, the merger event can provide an excellent window of opportunity to alter the “corporate personality.” Because a merger produces so much destabilization—and since it primes people to expect change—management can seize the moment and achieve significant cultural shifts.

This requires purposeful, well-executed moves, however, plus a good sense of urgency.

When the huge Tenneco, Inc., conglomerate acquired Houston Oil and Minerals Corporation, it made the timeworn pledge to keep the companies separate. But, as often found, it was a promise on which the acquirer could not deliver. Houston Oil and Minerals personnel found that being governed by one of the country’s biggest conglomerates meant they had to contend with a highly structured, bureaucratic parent firm that operated through a strict chain of command. The emphasis on budgeting and forecasting created massive amounts of paperwork. Incumbents complained about the system being impersonal as well as extremely frustrating, and Tenneco’s insistence on a more cautious exploration program added to people’s ire. Houston Oil and Minerals had a casual, freewheeling culture that nurtured aggressiveness and rewarded entrepreneurial spirit. The dramatic differences in corporate personality and organization structure caused people to leave in droves. Tenneco reportedly made a respectable effort to hang on to Houston Oil and Minerals employees, but in the end felt compelled to renege on its earlier commitment. A company memo explained that because of the loss of 34 percent of Houston Oil and Minerals management, 25 percent of its exploration staff, and 19 percent of its production people, it was impossible for the acquisition to remain a distinct unit.

Perhaps Tenneco could have done a better job of planning its postacquisition strategy. At the very least, it should have shown greater respect for the way the merger integration activities intruded on the corporate culture of the target firm. One of the most common merger problems—and one that is apparent here—is the “violation of expectations” that alienates people in the acquisition. An acquirer raises false hope by assuring incumbents that nothing will change and that they will be allowed to conduct business as usual. Then the cultural conflicts begin to surface, antagonism toward the parent company mounts, and the risk of merger failure increases.

Variations in Operating Style

Companies can experience a very difficult post-acquisition adjustment process simply as a result of having different operating styles. Cultural variations may not be pronounced per se. But, for example, if one organization is highly decentralized and the other is accustomed to strong centralized control, there will be problems to work through. Operating strategies and practices of the two parties to the merger/acquisition can vary in a variety of other ways, too.

Naturally, the more discrepancies that exist and the more pronounced these are, the greater the risk of failure.

Integration strategies should be planned with the following thoughts in mind:

- People, quite possibly in both companies, will be threatened and frustrated. The longer this emotionalized atmosphere lasts, the more damage it does to productivity and profitability.

- Training will be necessary if the acquired firm’s modus operandi must conform to parent company practices.

- Employees adjust better if they are given a good rationale for making the operating changes.

- Top management should analyze whether there really is a need to reconcile the two approaches. This requires systematic data gathering and deliberation.

- Top management should understand that speedy integration helps people adapt to the required changes.

Employees in a company that has been led by a single dominant figure, perhaps an owner/entrepreneur, frequently feel lost when the company is acquired by a large, impersonal, and highly diversified conglomerate. Likewise, a loosely managed, highly individualistic firm has a wrenching adjustment process once it weds a bureaucratic and highly structured organization.

Westinghouse Electric Corporation, an active acquirer, submits that it has been overwhelmingly unsuccessful in its efforts to retain the entrepreneurial owner/manager of the small and medium-sized business. An in-house memo states:

The reason is not difficult to see. At the same time that we provide such a man with independent, moderate to substantial wealth, we impose upon him seemingly onerous constraints on his freedom to run “his” business as he had previously done. Overcoming having given that person both the motive and the means to leave you requires strong action if it is to be successful.

Situations like these call for the integration strategy to include coaching for parent company executives on how to make entry into the acquisition. It only takes a couple of false starts (for example, confusion regarding reporting relationships and lines of authority) and the slightest display of arrogance or insensitivity for complications to develop. Westinghouse feels that its success in securing the long-term commitment of current owner/managers is directly proportionate to the amount of time it spends during negotiations on the following:

- Talking to the owners about Westinghouse’s expectations for the business.

- Listening carefully to their stated expectations.

- Discussing alternatives and contingencies.

- Above all else, describing fully and fairly the management controls, procedures, delays, and frustrations they may encounter after Westinghouse assumes control.

Chapter 1

Problems in Buying a "USED" Company

MANAGEMENT HEADACHES

Management of virtually any business enterprise will find there is no shortage of problems to contend with at each stage of the organization’s life cycle. Whether it be the start-up of a new venture, the struggle during the early years to establish a niche in the marketplace, the effort of a mature firm to fend off aggressive new competition, or the trials of managing mergers and acquisitions, the people in charge have their work cut out for them. But in making an acquisition, not only do top executives end up buying someone else’s problems, the merger event creates a host of new headaches as well.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF MERGER /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

A categorization of different merger/acquisition situations makes it much easier for management to anticipate the problems that are most likely to occur.

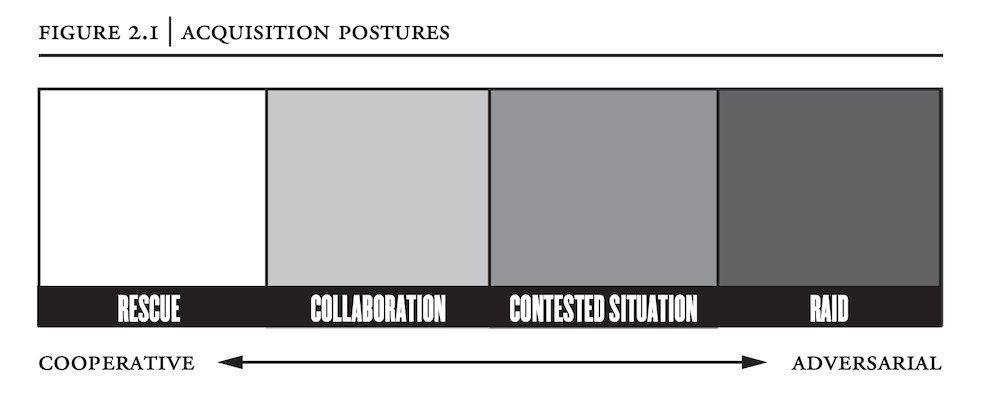

Four distinct acquisitional postures can be identified (see Figure 2.1). Each one has its idiosyncrasies plus unique implications regarding how management should gear up to cope with the difficulties that routinely develop.

The four broad categories of mergers are rescues, collaborations, contested situations, and raids. As Figure 2.1 shows, the rescue represents the most cooperative interface between acquirer and target company. At the other end of the continuum is the corporate raid, the most adversarial takeover situation. All four scenarios create adjustment problems for the acquisition. But the nature of the takeover determines to a large extent how severe the blow is, how long the trauma lasts, and the extent of damage to corporate health.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF MERGER /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

THE RESCUE

Actually, there are two different types of rescue operations. Frequently, a rescue develops in response to a raid that has been initiated by another firm, sending the target company executives scurrying in search of a “white knight.” The second type of rescue occurs as a financial salvage operation. In both situations, the to-be-acquired firm is casting about for help, looking for relief of some sort. The purchasing firm, therefore, is basically viewed as a welcome party. Still, there are almost always some mixed feelings on the part of the firm being acquired. Being rescued ordinarily is just the lesser of two evils, not what the target company would choose if it had any good alternatives.

Looking for Daddy Warbucks

The organization problems and management actions in the white knight scenario are very different from the Daddy Warbucks situation. Here the acquired firm is on the brink of financial disaster, or at least suffering from a lack of key resources (usually monetary). The very nature of the problem suggests that the company has some significant weaknesses. There probably have been fundamental mistakes in the way the organization has been run. Incumbent management usually has to stand responsible for the negative state of affairs and cannot be counted on to turn things around.

Odds are that the top management team in the acquisition has already taken its best shot at running the company. Otherwise, the firm would not have gone looking for a financial savior in Daddy Warbucks. The obvious question then becomes, “If these managers are responsible for bringing their company to this dire point and have proved incapable of overcoming problems of their own making, should they be entrusted with the husbandry of any new funds Daddy Warbucks invests in it?” The acquiring organization may be quite flush, but who wants to throw good money after bad?

In this rescue operation, quite a few members of the existing management team may be politely asked to leave. Naturally, there is fear in the hearts of some executives when it becomes obvious that an unknown number of people occupying the management ranks will likely be replaced. Employees in the acquired firm sense an acute loss of leadership, too, as their familiar standard-bearers leave the scene. Employees are understandably threatened by the prospect that the new owner may choose to deal with the financial problems by such actions as selling off a division, shutting down a plant, doing away with two layers of management, or cutting back the overall workforce by a large percentage. These are logical concerns.

This type of rescue is one of the two merger situations that require the most intervention by the parent firm.

On one hand, people in the acquired company realize that things have reached the point where sacrifices will have to be made to be merged by rescue. And the people in charge have decided that the trade-offs tilt in favor of being taken over by another organization. But there are always some employees who feel they would have been better served by not being acquired. They would prefer to stake their chances on surviving through alternative means. Thus, even the most benevolent Daddy Warbucks is likely to meet with varying levels of resistance in carrying out the financial rescue.

If the acquired firm is on its last financial leg, the rescue may generate a broadly felt sense of relief. Morale may improve. A new sense of challenge and anticipation may be apparent and certainly should be capitalized on by the acquirer. But at the same time, the parent company should (1) gear up to cope with pockets of resistance and (2) be prepared to counteract feelings of excessive dependency on the part of other personnel.

When a financially ailing company goes looking for Daddy Warbucks, the acquirer certainly needs to know the extent of its own resources. It needs to respect the limits of its ability to invest money and management in the new acquisition. Invariably, some type of rehabilitation, often a substantial degree of organizational change, is required. So, although the rescued firm may come at a bargain price, it usually carries hefty risks as well.

In this rescue exercise, the two companies do cooperate to a high degree and enter into the merger by mutual preference. But the target company is still, in a sense, a vanquished firm. There are likely to be tender egos resulting from this, together with a prevailing sense of defeat throughout the organization. In this atmosphere, there is a critical need for Daddy Warbucks to do more than tighten things up financially or even throw some new money around. People in the acquired organization need help in rebuilding their corporate self-esteem. Their pride needs to be restored and their motivation regenerated. They need strong leadership and a well-defined sense of direction. And with all of this, the sooner the better.

Rescue by the White Knight

In this scenario, we find the target company running for cover. It’s a panic situation; and under careful scrutiny, the outcome usually carries the tell-tale signs of decisions based on expediency. Time pressures rarely permit adequate analysis of the situation. The people in charge do a poor job of weighing the pros and cons and fall short in terms of searching for alternatives.

To get a quick gauge of the sort of problems this situation produces, think of it as involving impulse buying and panic selling.

To begin with, this suggests that many important issues get glossed over in both parties’ haste to justify and finalize the deal. And since there is such a shortage of data gathering and critical thought beforehand, there has to be much more of it after the purchase has been consummated. When the smoke clears, permitting a more relaxed and objective appraisal of all aspects of the situation, the flaws in the fabric of the agreement become much more visible. Now it’s time for the selling firm to begin second-guessing the wisdom of moving so rashly in the direction of the new parent company. Meanwhile, the white knight may begin to suffer buyer’s remorse.

One of the large mergers of the 1980s involved Conoco, Inc., Seagram, Mobil Oil Corporation, and E. I. Dupont de Nemours & Company. With two corporate raiders and a white knight involved, it appeared there was something for everyone. Certainly the stakes were high, but it was not a case where the winner took all. Conoco scrambled to elude the corporate clutches of first Seagram and then Mobil Oil, but the aftermath provided hard data that rescue has its own risks. DuPont prevailed in its offer, only to find its own independence threatened by possible loss of control to Seagram. Top management had to face a barrage of criticism from shareholders who were irate about their sagging stock prices. DuPont looked uneasily at its bankers and delicately pleaded for peace with Seagram, still a major stockholder. Meanwhile Conoco employees began to reassess their careers and wonder who would be the first to go, as it was apparent that the new owner would be divesting certain parts of Conoco in an effort to improve the financial picture.

Certainly this type of rescue is likely to generate many post-merger surprises. Quite a few significant issues that are not addressed or that are inadequately dealt with during the negotiations remain to be hammered out by the two firms. Usually both the rescuer and the acquired firm find themselves having to make compromises nobody foresaw. Ground rules that were not established regarding how the two firms will live together have to be determined. And whereas before the papers were signed everyone seemed quite cooperative and eager to strike an agreement, now the gears seem to grind much more slowly, and a far more cautious spirit prevails.

Often the management teams from both organizations feel compelled to strengthen their respective firm’s position, realizing they may have acted a bit rashly in their haste to make the deal acceptable to each other. The acquired firm, in particular, is prone to feel in retrospect that the new sense of safety came at too dear a cost. Personnel in the rescued company show an almost immediate transition from a sense of relief to wariness. Throughout the organization, people begin to wonder, “What have we done?” Now that the fearsome threat of the corporate raider has been eliminated, increasing prominence is given to the new threat that the white knight will take advantage of the situation.

So the white knight rescue is a little too much like a weekend Reno marriage. Without the traditional courtship period where people (or companies) have more opportunity to get to know each other and work through important differences, the “little period of adjustment” that routinely goes with marriage can become a long, drawn-out, and gut-wrenching experience. It is worth remembering that quick marriages are typically the hardest to make work.

In the aftermath of the white knight rescue, there is a powerful need for top management to take steps that ensure the two organizations will get to know each other. There will be a need to work through the many aspects of how the two companies will interact. This may point to the value of analyzing the compatibility of the two firms’ different cultures, operating practices, and the like.

Undoubtedly, top management needs to work hard to sell the idea of the acquisition to people in both companies. Finally, the white knight rescue needs to be viewed as one of the rare acquisitions where the parent company might—just might—take a hands-off stance for an indefinite period of time. Certainly if the new acquisition is a successful, smoothly running operation, extreme care should be exercised in the way it is handled.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF MERGER /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

COLLABORATION

By far, the biggest percentage of acquisitions fall into the category of collaboration. One company wants to buy and the other company wants to sell or is persuaded to sell, so both parties approach the bargaining table of their own choosing. It is not a situation like the rescue or raid, where one of the firms has its back to the wall and ends up with a new parent.

Other identifying characteristics of the collaboration are that the acquirer does not use surprise tactics on the target firm, nor are heavy-handed measures used. Rather, both parties strive to employ diplomacy, goodwill, and negotiating finesse in striking a deal that represents a fair exchange.

Usually, the negotiations are carried out with mutual respect and strong interest in doing business with each other.

These are important points because, with more goodwill going into the efforts in the negotiating stages, there is likely to be more of a positive atmosphere as the two companies come out of the deal.

Johnson & Johnson is one acquisition-minded company that has consistently applied a collaborative approach. Management has chosen to go after friendly deals. One of the major dividends of this strategy is that Johnson & Johnson has developed a reputation as a very desirable suitor. Companies approach Johnson & Johnson asking to be acquired by an outfit that’s built a name for itself because it treats people well and lets them run their own deals to an unusual degree.

Johnson & Johnson seems to have judiciously weighed the pros and cons of the various acquisition tactics and decided to follow the straight and narrow path of collaboration. This sort of merger/acquisition scenario provides a pretty respectable base from which to build. There will always be some ambivalence or mixed feelings on the part of the firm being acquired, but overall the positives are viewed as outweighing the negatives. Collaboration is a pretty non-adversarial situation.

Why is it, then, that employee concerns are still so much of a problem? For one thing, the people at the top may be sold on the deal, but fail to sell it to the people below. It may represent a win-win proposition for the two companies, but top management should never assume this is understood by people who have not been privy to the negotiating sessions wherein the agreement was engineered.

It is almost impossible to overcommunicate in the merger arena. Obviously, top management must employ discretion and a careful sense of timing in the handling of certain information, and it is risky to make very many promises or strong statements. But apart from that, usually the more information that can be shared, the better. It is difficult to find a company in the stages of being acquired that could not benefit from a better communication process.

Collaborative mergers and acquisitions are often jarring experiences because of poor follow-up management. In other words, while there was good negotiation, there is bad integration. The delicate footwork manifested in the sensitive process of making the deal disappears. Parent company management may breathe a sigh of relief with the opportunity to get back to “business as usual.” But people in the acquired firm know it’s a new ball game. They are like a raw nerve with regard to how they are being handled by the new owner, who so characteristically quits tiptoeing too soon.

Collaboration ordinarily involves the most courtship. In fact, the pacing is part of the collaboration itself. As a well-known executive in one of the country’s most acquisition-minded conglomerates said,

“Timing is everything.”

If the acquirer pushes too hard, a raid can develop. The timing has to please both parties, and as a rule, intensive efforts go into talking through the marriage plus the plans for the post-merger relationship. Generally speaking, collaboration—more than any of the other categories—is a merger condition in which the autonomy of the acquired company is most likely to be preserved.

Usually there is less need for intervention on the part of the parent. Thus, in this merger situation, the conditions are most appropriate for “management deals”—contractual arrangements designed to retain key executives.

Because of these practices, the mergers that come about through collaboration typically suffer the least from “post-merger drift,” the customary sag in productivity, morale, and operating effectiveness. Both parties to the merger have more ownership of the decision and therefore more commitment to making it all work.

This also suggests, however, that the acquired firm could be quite resistant to changes or interventions designed unilaterally by the new owner. Such intervention is usually perceived as an oppressive, inequitable move that violates the collaborative spirit that first gave rise to the merger. It is somewhat ironic in that the collaborative precedent established early on hints that this is the way the two firms are going to relate as time goes by. But it is unlikely that the parent company management will want (or be able) to interact with the acquisition in a collaborative manner under all circumstances. So when the precedent is not followed, management in the new acquisition gets jumpy as well as defensive. Since lower-level people in the acquisition are carefully watching their superiors, they too begin to resonate with the same negative vibrations. This sort of “collaboration backlash” is a phenomenon that acquirers will find almost impossible to avoid entirely.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF "MERGER" /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

THE CONTESTED SITUATION

The distinguishing difference between this acquisition approach and collaboration is that here only one of the two parties has a strong interest in making the deal, or the two firms want very different deals. Also, a contested situation may develop when there are multiple suitors who keep upping the ante for a target company. Often the firm under consideration is a reluctant bride but is unable to successfully defend itself against a takeover. The 1996 battle over Conrail provides a typical example. CSX seemed to be on the inside track, with merger negotiations proceeding peacefully. Then Norfolk Southern derailed the deal with a competing $10.4 billion bid that won shareholder approval. Conrail and CSX were left wondering who would end up owning what.

In contested situations, the negotiating can become very aggressive. There is plenty of resistance, but it is more depersonalized than that found in the raid.

Here, the battling between the two firms remains more logic-based and not as emotional as it is in the raid.

Probably the major difference between these two most adversarial takeovers, though, is that in the contested situation there is less of a feeling that there is a victor and a vanquished. It is common for both parties to walk away basically content with the deal they strike. In that regard, it remains primarily a win-win encounter, and the aftermath reflects an important spirit of cooperation. There may well be a strong flavor of opportunism in the behavior of both sides to the merger equation. But in contrast to the raid, the contested situation gives management in the target company a much better chance to emerge as heroes rather than as martyrs or losers.

By the time the deal has been finalized, however, the troops in the acquired firm often are quite battle weary. The bidding contest that marks this merger fray can be very stressful and unsettling. Ambiguity mounts quickly, and employees have a tendency to lose their job concentration ascthey watch all the fireworks. Concern for their own careers can becomecquite intense if a company vying for control implies that a takeover wouldcbe followed by divestitures, shutdowns, consolidations, or layoffs. The contested situation, like the three other merger types, typically produces a slowdown in productivity and organizational momentum even before a deal is consummated. Almost all merger/acquisition environments give “people problems” a head start on management.

The bidding process for the Chicago Sun-Times created precisely this kind of turmoil. A local investor group headed by James Hogue (the incumbent publisher) saw its offer being shunned in favor of a higher bid by Australian publisher Rupert Murdoch. A few months earlier, the owners had stated that Murdoch would be an unacceptable bidder, but apparently his higher offer proved a persuasive argument. Still a third would-be buyer emerged at the last minute with an even higher bid, but that overture got a cool reception. As the acquisition contest wore on, employees first became distracted, then worried about major staff cutbacks that were rumored, and finally, openly critical of the impending sale to Murdoch. Pessimism led to a wait-and-see attitude and fomented a rapidly building atmosphere of resistance throughout the workforce.

Contested acquisitions, together with some rescues and most raids, generate enough stir to get quite a bit of attention. Frequently, a few of the heads that are turned belong to executive recruiters. And in all the commotion of a contested situation, or a raid in particular, the search consultant often finds several high-talent executives with a rapidly growing interest in considering career opportunities elsewhere. This can help create a talent drain and leadership vacuum that cripple the acquired firm’s effectiveness in the post-merger environment.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF "MERGER" /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

THE RAID

Probably no one would choose the hostile takeover route as a preferred method for making an acquisition. Now and then, an executive may be invigorated by the thrill of the chase, and it can feel good to come out on top. But the headaches usually outweigh the ego gratifications.

In this merger scenario, the adversarial climate is at its peak, with the result being maximum resistance on the part of the target firm. Typically, an intense emotional component is interjected into the battle for ownership. Often, the defense becomes desperate. The propaganda mills in both companies pump out charges and countercharges. It is bad enough that accurate communication is a scarce commodity even in the most benevolent acquisition environment. Here, the truth gets stretched ridiculously out of shape, and the rumor mill roars out of control.

A routine practice is for management in the besieged organization to generate strong antagonism among its employees toward the corporate raider.

Invariably, the employees seem to love it. They defiantly wave their own corporate flag, rallying behind their leaders and becoming even more cohesive in the struggle against a common, outside enemy. This interesting phenomenon occurred in response to Wells Fargo’s takeover attempt involving First Interstate Bank in California. Target company management proclaimed that the merger would have a disruptive effect on employees, hurt morale, and create an uncertain future for the firm. Then First Interstate went even further, soliciting reinforcements from politicians, employees, customers, and the media. Employees protested on the steps of city hall and petitioned the mayor’s office in Los Angeles, attempting to keep Wells Fargo from completing its bid. The merger fight was a draining, expensive, bitterly fought duel. And though Wells Fargo won the battle, the war obviously was not over. Next came the subtle resistance, the guerrilla warfare in the corporate underground.

It is true, however, that when this sort of defense works, it can be a very positive event for the target company. A more intense corporate spirit develops, and management emerges with stronger backing from the employees than it had before the raid commenced. Workers swell with enhanced pride, and morale ordinarily notches up.

The target company’s executives can almost always whip up strong employee concern and bitter resistance to the takeover. The risk inherent in this defense tactic is substantial, though, as the warnings top management gives to its workforce can be a self-fulfilling prophecy if the hostile takeover is successfully accomplished by the raider. The scary scenarios target company executives develop in playing to their people’s fears are potential attitudinal monsters; management’s creation, they sometimes become management’s curse.

When the fierce defense fails, many problems develop out of the residual antipathy. The hard-fought battles usually leave behind a lot of wreckage.

Employees cannot make the psychological shifts necessary to go blithely from battle to brotherhood in a few days

The raid creates winners and losers, but it does not necessarily end the fight. Long after the legal documents have been signed and media attention has faded away, the war may continue. So there is a catch-22 to the corporate raid, and it goes like this: Acquiring a company to sustain growth and nurture the corporate base, when undertaken through hostile action, creates negative management conditions that actually hamper expansion. The defense designed to ward off a corporate raider does not vanish in the event that it fails. The minefield planted to protect against the acquirer remains to plague management in both companies.

Top management in the newly acquired firm finds itself in somewhat of a box. Having led a very antagonistic, emotional battle against the company that is now the new parent organization, the management team that has been taken over must either recant, thereby losing credibility, or resign. In either event, the leadership of the acquired company is in trouble. As in war, the leader of a conquered company must try to alleviate the enmity and adversarial climate that he or she has orchestrated. The other alternative is to abdicate leadership.

In corporate wars, the best and brightest often flee to friendlier settings.

Talent leaves first in the aftermath of hostile acquisitions, and these organizational refugees may leave behind only a shell of a management team and a workforce plagued by resentment and uncertainty. Even in amiable acquisitions, “people problems” rank right up at the top along with negative economic conditions as a prime reason for merger tangles. Resisted takeovers are even more prone to human-resource failure.

Top management in the parent company also finds itself in some operational straitjackets. On one hand, there is a need for fence mending. But because the newly acquired managers and employees are somewhat recalcitrant and begrudging, they require more policing. So the raider is often compelled to impose tighter controls and send in its own managers to function as “occupation troops.” That can further alienate and demoralize target company personnel, however, resulting in management bailouts and sabotaged productivity. Corporate raiders might wish to bolster morale by promising their new corporate roommates that “management will not be changed, things will remain the same, it will be business as usual.” It would be nice if things could operate like that, because in hostile takeovers employees are especially sensitive to restructuring. But it is the very thing employees make more necessary by their unwillingness to adapt.

The raiding company implicitly sets a management philosophy through the way in which it captures its quarry. In essence, the raider has made a “corporate intervention” even before it actually succeeds in the takeover. A management policy has already been demonstrated by the acquirer. Thus, it becomes very difficult to collaborate after the raid has been carried out. Management in the parent company is making a very hollow statement when it assures everyone “We don’t plan to make any changes.” In reality, the changes have already begun. The target company has to make quick changes in some of its behavior because of the acquisition threat. And the pre-merger climate virtually guarantees that further changes will be forthcoming in the post-merger period.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF "MERGER" /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

THE INCLINE OF RESISTANCE

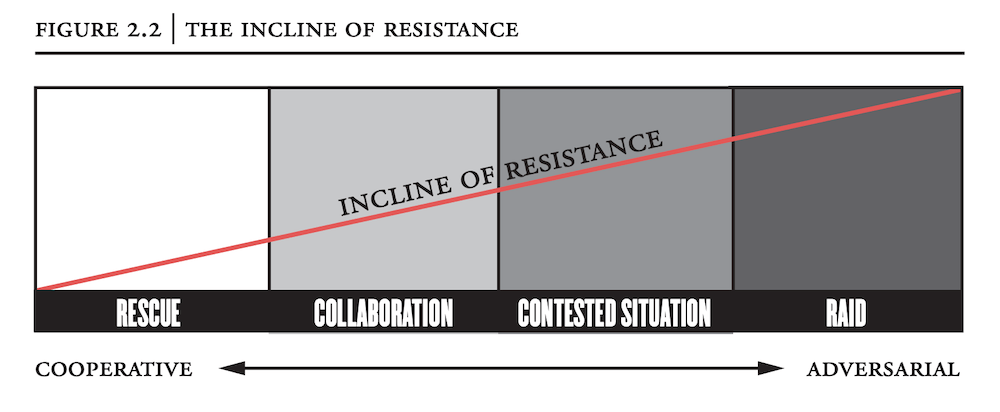

The degree of resistance to the acquisition becomes greater as one moves from a relatively cooperative merger to the more adversarial events. The incline of resistance demonstrates

- the intensity of opposition to the other party’s merger objectives and

- the amount of resources (money, energy, time, and so on) expended struggling with the merger event (see Figure 2.2).

Both the acquirer and the acquiree demonstrate forces of resistance that range from negligible to extreme. A company being rescued, as a whole, usually welcomes the acquirer. Even within the rescue, however, there will be at least passive resistance to doing things a new way. Furthermore, some people in the target firm will invariably oppose the idea of running into the arms of Daddy Warbucks or a white knight.

The incline of resistance peaks out in the hostile, defensive environment of a raid, and parent company management needs to be able and ready to meet this challenge. Obviously, much more will be required of parent company management in acquisitions where the incline of resistance is most pronounced. A collaborative acquisition might prove to be a successful venture, whereas a hostile takeover of the same firm might lead to failure.

As the incline mounts, both initial negotiation strategies and eventual integration policies must change.

The more resistance increases, the more people on each side become onesided. That is, they become more attached to and have more personally invested in their particular side of the issues. This is just one of the common sociological aspects of mergers and acquisitions.

The higher the incline of resistance goes because of the nature of the acquisition environment, the longer it usually takes for that resistance to subside. Raids and contested situations usually involve the most prolonged post-merger period of opposition. Those two types of takeovers call for the most concerted efforts by parent company management to alleviate the problems. Ordinarily a one-shot attempt will not be sufficient to overcome the polarization and adversarial hangover that remain. Instead, management should design a strategic integration program that respects the magnitude of the problems and that holds promise for getting people from both firms to the point of pulling together for the good of the merged firms.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF "MERGER" /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

THE RISK CURVE

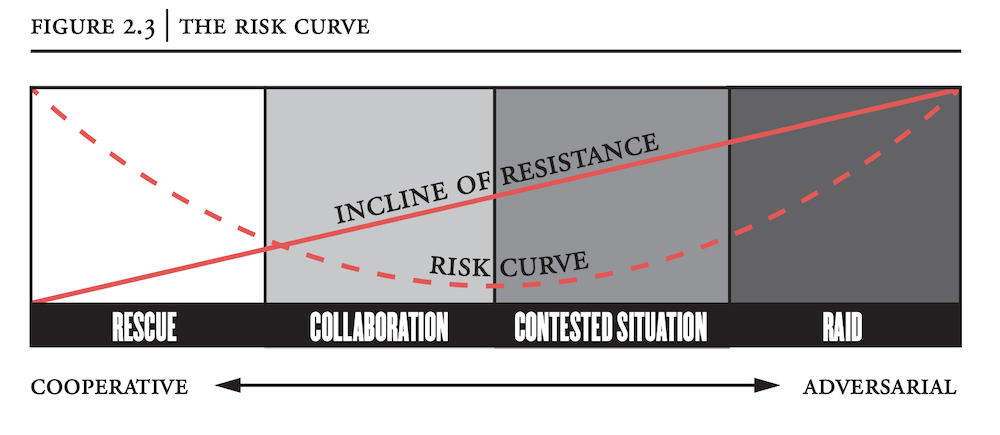

While the incline of resistance steadily increases from the rescue type of acquisition through the raid situation, the amount of financial risk that management has to contend with tends to be greater at each end of the acquisitional continuum. In the rescue, the acquirer gains a firm that is often beset by financial woes and possesses a dearth of leadership.

The raid situation almost guarantees overt resistance and threats of bailouts by the most capable people within the organization. At a time when top talent is needed to stabilize a company acquired through hostile action, those people look elsewhere for career opportunities.

In the rescue event, it is less likely that people will leave. Unfortunately, incompetent individuals who have created the conditions necessitating a rescue are sometimes difficult to dismiss. Rather than demonstrating explicit hostility toward the acquirer, companies being rescued often have a workforce characterized by passivity and inertia. And just as that contingent of people demonstrated a prior inability to turn things around on their own, they frequently prove to have real difficulty adapting to the needed changes once new management takes over.

The risk curve (see Figure 2.3) may be misleading on one point—all acquisitions involve financial risk. Collaborative or contested acquisitions can result in financial failures, just as can rescues or raids. This curve assumes that, all things being equal with regard to the external economic climate, the risks of failure are greater with the rescue or raid situation than they are with either of the other two merger classifications.

Corporate raiders often have to spend more than would be desired to obtain a reluctant firm and thus become financially threatened by the debt burden that must be assumed. Also, the resistance gradient is at its highest point in the raiding scenario, and employee resistance can sabotage even a fairly well-financed takeover. In the more cooperative rescue mode, risk is great because of the nature of the takeover. It often involves saving a company that is flirting with insolvency or that must shore up sagging or departing leadership. The vitality of such a firm is seriously in question.

Chapter 2

A CLASSIFICATION OF "MERGER" /ACQUISITION CLIMATES

NEGATIVE SYNERGY OF MERGERS

A common argument offered in favor of mergers and acquisitions is that a positive synergistic linkup can be achieved. Company A buys Company B, and their combined resources represent more than the sum of their individual parts. The synergistic sword cuts both ways, however, and the downside risks typically are not explored in as much depth as the upside potential.

Regrettably, two companies’ problems can be just as synergistic as their potentials. One firm’s difficulties plus the ailments of the other cannot be conveniently added up to a neat sum total. The merger brings with it a new and unique set of previously nonexistent difficulties.

Over the years, top-management teams have been prone to disregard the negative synergy of mergers in their strategic planning relative to growth by acquisition. Corporate planners focus their analysis primarily on what the buyer and the target company can each bring to the merger, with little formal study being aimed at ascertaining what the merger event itself will do. In fact, the merger is a corporate intervention. It should be respected as a new force that management must contend with. At times, it stands as a rather cataclysmic influence. When the decision to acquire or merge is first being made, those realities do not exist. But newly forged corporate bonds bring new realities and a fresh set of facts.

Management in the acquiring company should take pains to play out various merger scenarios in careful detail. More thought and war gaming should be devoted to an analysis of how the companies can be combined. Contingency planning should be expanded to take into fuller account the negative synergy that may develop.

This is particularly true in the corporate raid because in the hostile takeover the two parties are not working together in a collaborative fashion at all. They are not putting their heads together to figure out how to make the deal work. Thus, contingency planning is extremely one-sided. The acquiring company—and for that matter, the target company as well—must lean much too heavily on conjecture. It is bad enough if the adversary does not work with you. In the raid, the adversary is working against you. Each party to the merger throws surprises into the situation. Each company is at odds with the other’s line of reasoning. Both parties are out to confound the other’s strategies.

Ordinarily, merger planning and decision making are based most heavily on the financial considerations involved. But the success or failure hinges very heavily on the intentions of both sides in the equation. And in a hostile takeover attempt, neither one of the management teams has sufficient insight into the intentions of the other. This makes it extremely difficult to predict what’s coming.

Chapter 3

PSYCHOLOGICAL SHOCK WAVES OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

When merger rumblings are heard in the organizational jungle, the natives get restless. The work climate changes. This change is a given. It is not something that top management in the acquiring firm can allow or prevent at will.

The magnitude of change can be controlled to some extent. But whether or not there is change at all simply is not subject to debate. Everyone who will be affected by the merger/acquisition—and top management in particular—should accept this fact and concentrate on how to come to grips with it.

Effective management of mergers and acquisitions demands that the people in charge be prepared for the emotional shake-up accompanying this kind of organizational growth. When word goes out that an acquisition is in the wind, there is a measurable impact on employee attitudes, feelings, and work behavior. The regrettable fact is that these shifts or changes—again, unavoidable—are for the most part negative. They reflect how a distressing psychological event has affected the lives of executives, managers, and the rank and file. Usually people in both companies, but particularly the one being acquired, must go through a major adjustment process. They have to adapt to a variety of new organizational realities.

But people often resist change. Changes they fear or changes that are not of their own making ordinarily elicit the most resistance. This is a key point because most people whose company has merged or been acquired had no part in that decision. Not only did they have no say in the matter, they often were taken completely by surprise.

Employees commonly get blindsided, emotionally jolted, by the news that their corporate family is being reshaped and given a new authority structure. Feeling no personal ownership of the decision someone made to merge or sell the company, employees’ commitment to support the idea may be weak.

The heightened state of uncertainty that is instantly created pervades the work climate. People get jumpy. They wonder when the other shoe will fall. And because they fear additional surprise—particularly regarding their own career safety—they instinctively move to protect themselves.

The merger and the potential changes it brings are resisted deliberately as well as unconsciously. Some people are very outspoken and overt in expressing their dismay. Instead of trying to conceal their opposition, they purposefully ventilate it, perhaps in hopes of short-circuiting the deal. While some choose to openly express their shock, anger, and frustration, other employees could not hide their feelings if they tried.

The unconscious resistance, far more subtle but often more pernicious and damaging in the scheme of things, is much more widespread. It is more passive in nature. It gets manifested in the job performance of people who would honestly assert that they wish to be cooperative and support the corporate marriage. But the hard facts argue convincingly that the unconscious resistance is there, and that it is taking its toll. It shows in morale, turnover statistics, productivity, loss of competitive advantage, deterioration in revenues, disappointing profits, and so on.

Even when people in the acquired firm make a concerted effort to adjust and embrace it, the merger can turn sour. Their coping behaviors tend to be highly self-oriented and thus dysfunctional as far as the organizational good is concerned. The things they do and don’t do in looking out for themselves are frequently incompatible with what the organization needs from them at that time. Much employee behavior that is well intentioned and even self-sacrificing runs counter to what needs to happen in a merger environment. But if management has not been trained to manage the change process, why should it be expected to play it by ear and get it right the first time around? Or even the second, third, or fourth time?

Chapter 3

PSYCHOLOGICAL SHOCK WAVES OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

KEY DYNAMICS SET IN MOTION BY THE MERGER

The merger/acquisition scenario is highly predictable in terms of the psychological dynamics generated. It helps if management knows this and knows what to expect. That is at least a first step in the direction of being much better equipped to deal with the situation effectively.

The shudder that moves through an organization when it is acquired is no peculiar or unique phenomenon. It is simply human nature in action. And since organizations are made up of people, top management can anticipate the key dynamics with great certainty.

Ambiguity

As the dust begins to settle following the announcement of an impending acquisition, a powerful new force begins to register its influence. This first dynamic is a climate of ambiguity. It reveals itself as a work atmosphere wherein there are far more questions than answers. People at all levels feel it as an information vacuum. There is a disconcerting lack of clarity regarding the corporate future and the further surprises or changes it holds. People also wonder about the role they as employees may or may not play in the upcoming scheme of things.

Even if higher management tries to alleviate this uneasiness by giving assurances about job tenure, a substantial amount of tension remains as people wonder about what new requirements might be made of them, what new reporting relationships might develop, and so on. Employees generally suspect there will be some sort of change in procedures, objectives, operating style, and the management structure.

This pervasive ambiguity stems quite naturally from two roots: (1) top management’s need (or felt need) to be discreet and (2) top management’s own lack of specifics regarding the ramifications of the merger.

Everyone is suffering from the unknown. And the truth is that even the president and board of directors do not have the power to satisfy everyone’s curiosity and rid the work environment of ambiguity. Furthermore in many situations, top executives usually consider it injudicious, possibly unkind, and maybe even illegal to inform people of the hard facts.

So a great deal of ambiguity, vagueness, or fuzziness builds up as the merger/acquisition situation unfolds. Some people have a psychological makeup that enables them to endure this kind of work climate reasonably well. Others find it extremely upsetting. Those employees who like order, generous job structure, a well-defined and predictable chain of command, and a clear sense of direction are inclined to feel dangerously adrift in the merger environment. All of a sudden, their world has become destabilized.

Weakening Trust Level

The second major dynamic that top management needs to understand is the lowered trust level in the company. Invariably, the announcement of merger plans will cause the affected parties to become more suspicious and wary.

One reason for this may be the rude shock often caused by the abrupt announcement of the merger. Employees quite understandably will often conclude that top management cannot be relied on to be sufficiently open and aboveboard about things that very directly affect the individual. Moreover, people at all strata in the corporate structure usually realize that the top decision makers know more than they are telling. Employees know implicitly that more surprises are forthcoming.

Personnel who previously were willing to give the company the benefit of the doubt now become skeptics, some even cynics. And those who were mistrustful or insecure to begin with may become downright antagonistic and paranoid. Those who had been quite willing to rely on top management to look out for the needs and interests of the average employee now feel obliged to change their perspective. Now everything that is done or said by key executives gets viewed with a more jaundiced eye.

Actually, this is a rational response. Weakening trust level is a monster created (and sometimes unnecessarily nurtured) by top management through faulty communication and insufficient candor. The bigger the initial shock and the greater the secretiveness, the more the trust level suffers. This leads to the third dynamic.

Self-Preservation

Merger/acquisition activity leads to self-preservation as a dominant motive in employee behavior. The weaker the trust level, the more visible the self-protective behaviors that surface. Particularly, those individuals in the middle management and executive ranks begin to deploy their personal armaments toward maximum protection of their individual careers. Rank-and-file employees may be just as troubled as those in leadership positions, but usually they give much less visible evidence of attempts to protect their jobs.

It is interesting to observe the myriad ways in which people strive to defend themselves. Some launch an aggressive attack, actively vying for position, and sometimes hoping to leverage themselves strategically into a position of even greater power and prestige. Others lie low and wait for the smoke to clear, preferring to maneuver carefully rather than attack boldly. And some calculate that their best odds for surviving will result from simply not offending. They deliberately move out of the line of fire and hope that fate smiles on them.

At any rate, self-protective behaviors result in many hidden agendas. These divert time and energy from the pursuit of company objectives. Also, top management finds it more difficult to direct an effective corporate offensive because all of a sudden it is much harder to predict what people will do. Employee behavior is founded much more on emotion and obscure motives, less on apparent logic or rational thought.

Chapter 3

PSYCHOLOGICAL SHOCK WAVES OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

THE EMOTIONAL IMPACT ON PEOPLE

Human beings instinctively seek to maintain control and predictability over their world and their immediate environment. The more ambiguous the work climate is, as in a merger, the more this human goal is sabotaged.

High levels of ambiguity lead to excessive uncertainty.

Employees become confused, less sure of themselves, and sometimes highly anxious.

Even after the initial impact of the shock has diminished, employees in the acquired firm are hit with repeated demands for change and adaptation. This invariably disrupts their established and previously successful adjustment to life, as they are beset by financial concerns, professional insecurities, and fear of the new as well as the unknown. These uncertainties, fears, and inner tensions do distinct damage to individual productivity. Regrettably, anxiety tends not to be a very constructive emotion. It inhibits creativity, interferes with one’s ability to concentrate, acts as a drain on physical energy, and frequently lowers the person’s frustration tolerance. Logical thought processes give way to emotionally colored problem solving and decision making.

The impact of a lowered trust level within the corporation is similarly negative. This, too, can provoke an unhealthy degree of anxiety. Tension mounts, contributing to the psychological stress load employees have to carry. Individuals may become more fearful or noticeably more angry, hostile, and defensive. Employee morale and attitudes are corrupted by this highly contagious mind-set that ravages the workplace.

When self-preservation becomes a primary concern, employee behavior reflects selfishness at the expense of a needed concern for the organizational good. Those personnel who suffer a sense of betrayal by top management commonly transfer their loyalties. The owner or CEO who may have been an important father figure for the organization may come to be viewed as one who abandoned his people, the implication being that one is foolish to place trust in top management (particularly if top management consists of outsiders).

Sometimes these self-protective behaviors lead to a variety of regressive acts on the part of employees. For example, some people withdraw. Managers may hole up in their offices. Employees may find superiors more inaccessible and may themselves invest less effort in communicating. Workers often exhibit a greater degree of emotional detachment vis-à-vis the firm. Thus, their commitment weakens and, along with it, standards drop and output diminishes. But detachment does represent one way of protecting oneself from being taken advantage of, hurt, or surprised.

In some instances, an entire department or work group becomes more close-knit as far as its own members are concerned yet more isolated from the organizational effort as a whole.

The important thing for management (in both the acquiring and acquired firms) to remember is that these are all legitimate reactions. Obviously, they are counterproductive and do a disservice to the organization, and they frequently create even greater problems for the employee. But they are understandable and predictable in view of the key dynamics that underlie them.

Chapter 3

PSYCHOLOGICAL SHOCK WAVES OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

NEGATIVE EFFECTS ON EMPLOYEE BEHAVIOR

As the psychological shock waves surge through the organization, they take their toll in operating effectiveness. Emotions—psychological factors—begin to bias behavior. Six major problem areas highlight the fact that top management is making a crucial error when it fails to deal expertly with the emotional issues in a merger or acquisition.

Communication Deteriorates

As the trust level in the organization drops, people begin to play their cards much closer to their chest. The information channels receive less input that is dependable. And the data that does circulate is more likely to be filtered, distorted, or edited out completely before it reaches its intended destinations.

It seems that virtually everyone has an increased appetite for information and a diminished willingness to feed honest accurate data to others.

Rumors rush in to fill the communication vacuum that develops.

There is no overall shortage of information, but much of what is there in abundance is erroneous, mere speculation, or both.

This problem of information warp is compounded by people’s exaggeration, fear mongering, and wishful thinking. Many silly notions are passed along from person to person, frequently embellished with each retelling. The traditional rules of gossip prevail—that is, truth gets distorted, unfounded ideas are reported as established facts, insignificant matters come to sound like high drama, problems are blown out of proportion, and so on. Some people intentionally twist the truth and circulate erroneous information. Their motive may be to sandbag higher management, sabotage a peer they see as a potential competitor, or protect themselves and perhaps justify their mistakes.

The rampant mistrust, wariness, and paranoia cause people to distort a lot of what they see and hear. As people become more skeptical and cynical regarding the validity of what higher management has to say, they are inclined to misinterpret and misperceive far more than they would under ordinary circumstances. Issues are emotionalized, and that contributes to data distortion. People lose objectivity as a result of their concern and ego involvement.

Top management is likely to experience frustration regardless of how honest it tries to be in communicating with employees at the various levels in the firm. To some extent, this is because people selectively perceive. Some hear only what they want to hear or what they expect to be told. Others construe beyond what top management actually says, reading between the lines and in the process reading more into a statement than was originally intended. Hints, subtle implications, or innuendos are mentally snatched up, fleshed out in much greater detail by the person’s imagination, and then thrown back in the face of the executive later on as proof of his or her lack of integrity. It is very common to observe employees mentally constructing the reality they (1) wish for or (2) fear.

It is ironic that top management probably never tries harder to be truthful than it does in the merger/acquisition arena and yet still fails.

There should be little doubt that top management genuinely wants to tell the truth. But frequently executives may not know what the truth is and, as a result, catch themselves (or get caught) in duplicity. It is important to remember that employees commonly are not feeling very congenial toward the owners and top executives after the announcement that an acquisition is forthcoming. Employees are expecting more trouble. And they are expecting more surprises from the people in charge. Furthermore, when the top executives talk, everyone else in the organization hangs onto their every word. In such circumstances, it is easy for the boss to make communication mistakes.

Because of the facades, faking, outright lies, and inadvertent misunderstandings, the organizational trust level is still further diminished. Weakening trust, in turn, causes more communication damage, and the downward spiral continues.